I like Valentine’s Day because it gives me an excuse to watch people talk about their loved ones. Their eyes start to rove around the room as they smile a little in spite of themselves and their shoulders relax. People are endearing when they talk about what is dear to them.

But the loves we celebrate at this time of year tend to rest around the same temperature — hot, heavy and romantic. Feb. 14 ought to be a time for us to celebrate all kinds of loves, past and present.

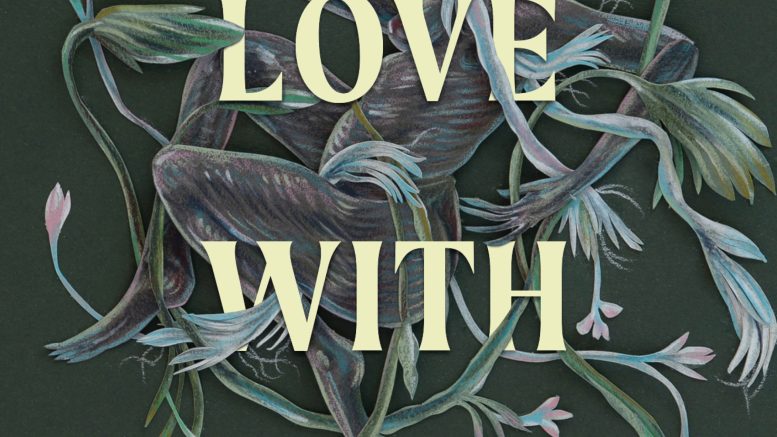

After making waves with Jonny Appleseed in 2018, Treaty 1 storyteller Joshua Whitehead’s latest virtuosic collection of essays Making Love with the Land certifies his visionary capacities while paying tribute to a variety of great loves in the writer’s life.

Part tribute to a love post-break-up and part generous disclosure of the storyteller’s journey to self-love, Making Love is a pensive assemblage of many of Whitehead’s cherished memories with people he loves.

Essay collections can be Frankensteinian in their make-up, often lassoing scattered published and unfinished pieces across an author’s life and ordering them together as loosely related opinion writing. But Whitehead’s essays cohere in style and subject, not just as afterthoughts piled together.

The essays also entirely sidestep divisions between fiction and nonfiction, and deploy an authorial voice of many attitudes rather than a monolithic one.

At times intimately confessional and at others just saucy, the voice brings the reader into confidence about everything from his reservations in private conversations to his euphoric connection to his two-spirit identity, as well as ongoing bereavements for loves long lost.

Making Love’s prose periodically drifts into a verse-like place and back again throughout. The result is a breathtakingly lyrical style that doesn’t just flow but soars through Whitehead’s ruminations. The collection begins with this musicality at the fore. The first paragraph in the opening essay “Who Names the Rez Dog Rez?” needs to be read aloud to let its rhythm breathe fully and to appreciate the alliteration spilling out of every line.

This musicality and detail in Whitehead’s writing extends to the multiple languages of Making Love. The book switches between Cree romanizations, syllabics and English often within single sentences.

“A Geography of Queer Woundings” in particular bubbles with Cree vocabulary and hops so quickly between languages that new words started to hold meaning for me not long after they were introduced.

As the inclusion of Cree romanizations suggests, Making Love’s bilingualism invites non-Indigenous — particularly white settler — readers to grasp the opportunity to learn and understand Indigenous languages and cultures outside of colonial languages.

While Whitehead’s focus is often joyful, colonialism stains many treasured memories.

In “My Body Is a Hinterland” Whitehead describes bringing his partner to Gimli, Man. as a way of sharing the dearer parts of Treaty 1 with him. What ought to have been a romantic evening is spoiled as the pair overhear other patrons at a bar making queerphobic and racist comments.

After that, Whitehead describes the poisonous amount of bird excrement in the nearby lake, resulting from flocks of gulls attracted to fishermen’s garbage. The author likens his body to the lake and the bigotry he has experienced to feces.

The reek of scat — ongoing colonial violence — can’t be ignored, and likewise the motif of crap runs throughout the collection.

However, the love Whitehead’s authorial voice holds for his culture, community and even himself makes life not only survivable but joyful.

“My Aunties Are Wolverines” is a powerful description of Whitehead’s grief in the wake of one of his matriarchs’ passing that wells up with a deep and abiding love for his late aunt.

The book offers the best experience the creative essay genre can give too — a feeling of connection with a kindred spirit.

Making Love has the precise focus of a documentary. Whitehead notates the most minute slices of his life into little histories with an attention to detail that weaves readers completely into the fabric of the writer’s inner world. The result is a multi-dimensional, highly sympathetic and profoundly human point of view.

“The Year in Video Gaming,” for example, is a reassuring testimonial on the normality of forming deep and medicinal attachments to Fire Emblem characters.

From long-term weather-worn residents of Manitoba to insomniac grad students, to anyone who has been subject to an ekphrastic exercise — writing poetry about art — in a writing workshop, Making Love extends a hand to a diverse audience.

The final essay in the collection briefly touches on one terrible Valentine’s Day Whitehead experienced post-break up, but like the rest of Making Love the essay gestures to the expansive possibilities for love and life beyond single romantic relationships without succumbing to cynicism toward romantic love altogether.

Making Love breaks the boundaries of genre, showing Whitehead’s breadth as a writer and a focused, unwaning voice.

It is at once a generous memoir, a critical intervention and a compendium of Indigenous knowledge wrapped in symphonic ecstasies.

Making Love with the Land is available at major retailers.