It goes without saying that British Columbia is rotten with hippies. Especially in summer, when the gentle people travel from many provinces and countries to attend a string of festivals, the Canadian expression of the flowering West Coast electronic festival scene. Here are some thoughts from my thesis notes, exploring the sacred elements in the landscape architecture of psytrance festivals.

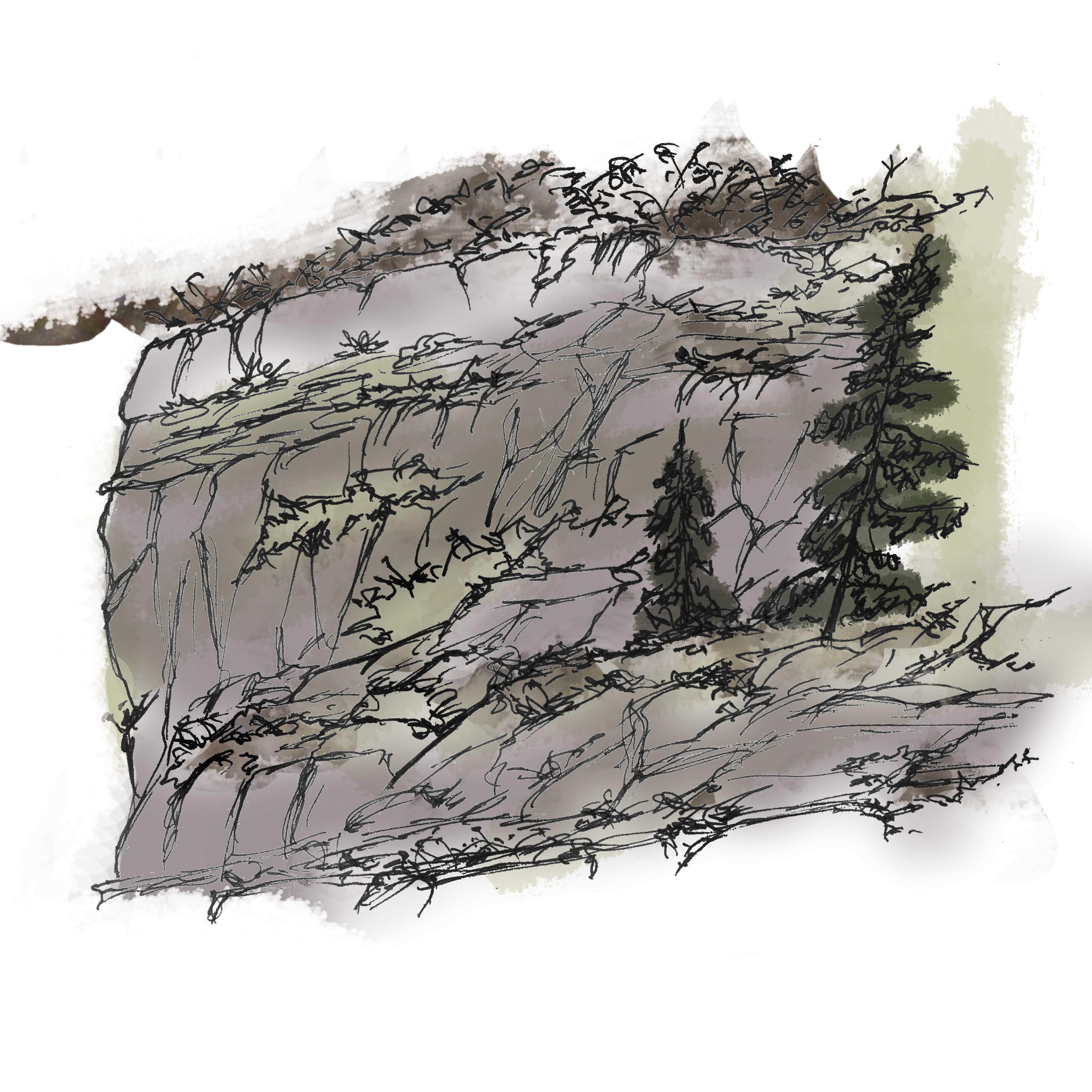

At the bottom of a gorge, a river roars smoothly by. People sit in small groups on the rocks shaded by cliff-side forests. Some talk and laugh softly in French, some play instruments, some stare out at the water. The smell of tobacco and weed mingle in the air, floating up to the tents and mandalas stretched between tall pines at the top of the steep trail that winds down to cool rocks.

Sylvan and peaceful, yet there is a heavy vibe in the air. Everyone present is focused on the moment – they are all of like mind. Hitchhiking is easy, as the locals are getting used to the sights of what I would describe as a series of interlinked modern pilgrimages: life is good.

Pilgrimages are holy because the journey takes on the character of the destination. The number of people travelling to, from, and between festivals in the summer is great enough, and has been going on long enough, that a particular style and community can be felt. For many of these travellers resting by that river, the same journey – at least to the same ultimate destination – is repeated year after year, becoming richer with meaning and memory, as traditions bloom slowly into spiritual significance.

The binding element – and goal of their individual pilgrimages – is the dance floor. Not a club and not available for the price of a ticket, this dance floor is a shared ceremonial space in which to enact rituals of sanctity. There, lulled to group consciousness by ecstatic dance, repetitive bass beats, and entheogenic sacraments, the weary soul rests and is renewed. Leaving, the participants are fortified to enact their shared vision of life in the world beyond the space delineated for the sacred – souvenirs taken home from the shrines of saints.

These souvenirs are seen in attitudes and in lived choices. Comfortable clothing, beautiful jewellery and tattoos, useful camping tools and light tents. A willingness to try going without, and eagerness at the chance to do more with less. Experience eclipses all physical things in value – to be in beautiful places, with beautiful people, doing beautiful things. To share the gentle knowledge of the sanctity of the world, by seeing the sacred in all things, and hopefully, to spread it.

The joy, exuberance, and community which began its life at festivals slowly seeps out into the landscape around it, instructions waiting to be read.

Each new visit by one of these travellers to a new dance floor is a chance to share experience, ideas, and hopes, fortifying and strengthening the community.

The festivals have workshops on ecological living, arts, and spiritual practices. Outside the workshops, participants are happy for the chance to learn from each other, to be inspired by each other. There is a palpable willingness to achieve personal growth, and the almost universal practice of dance, object manipulation, and meditation as acts of leisure.

There is a shared understanding that the richness of the journey contributes to the splendour of the destination, and the tongue-in-cheek knowledge that, for real travellers, the festival is everywhere, and the journey is replete with the sweetness of its end. The travel to the destination is undertaken to enrich that destination; once the destination is reached, the experiences and beauties known on the path to it can be shared with other travellers through dance, and as artful living.

There is an undercurrent of hope that, someday, somehow, the wider culture of the West can be made into an image of this lived truth, and that travelling holds the key to coming home.