Many acclaimed works of literature share the fact that they’ve been banned, at some time or another, in part for their sexual content.

Non-fiction

American sexologist Alfred Kinsey’s frank conclusions in Sexual Behavior in the Human Male included the study of homosexual activity and bestiality, topics not openly discussed at its release in 1948. For example, the book offers information on “pre-adolescent sex play,” asserting that at this age, “erection and orgasm are easily induced [ . . . ] erection may occur immediately after birth.”

Although it was a U.S. bestseller, the non-fiction book—followed five years later by its female equivalent—was banned in South Africa and Ireland, and was highly controversial due to its candid observations of human sexuality. Many sexual behaviours were illegal at this time, and some disclosed to Kinsey about being sexual abusers. Allegations of Kinsey encouraging these behaviours arose in the 1990s: “The act of encouraging pedophiles to rape innocent babies and toddlers in the names of ‘science’ offends.” In 1995, an American politician campaigned at the U.S. House of Representatives for a bill—which was denied—to investigate Kinsey’s research.

Poetry

Sex and rebellion found their poetic form in “Howl.”

Allen Ginsberg’s three-part poem deviated from traditional poetry in more ways than one. It strayed from the established notion of what poetry was. “Howl” includes lines such as, “who howled on their knees in the subway and were dragged off the roof waving genitals and manuscripts, who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and screamed with joy, who blew and were blown.”

An obscenity trial of the poem—against the original publisher of the poem, Lawrence Ferlinghetti—occurred. Ferlinghetti won the 1957 trial; the judge found “Howl” to have “redeeming social importance.”

“Howl,” an embodiment of the Beat Generation, essentialized the emptiness and restlessness of American life, and is an exercise of free speech.

Prose

Shielding children from each horrendous real life event’s respective literary depiction will not necessarily be beneficial; attempts to ban controversial material from schools are much too common.

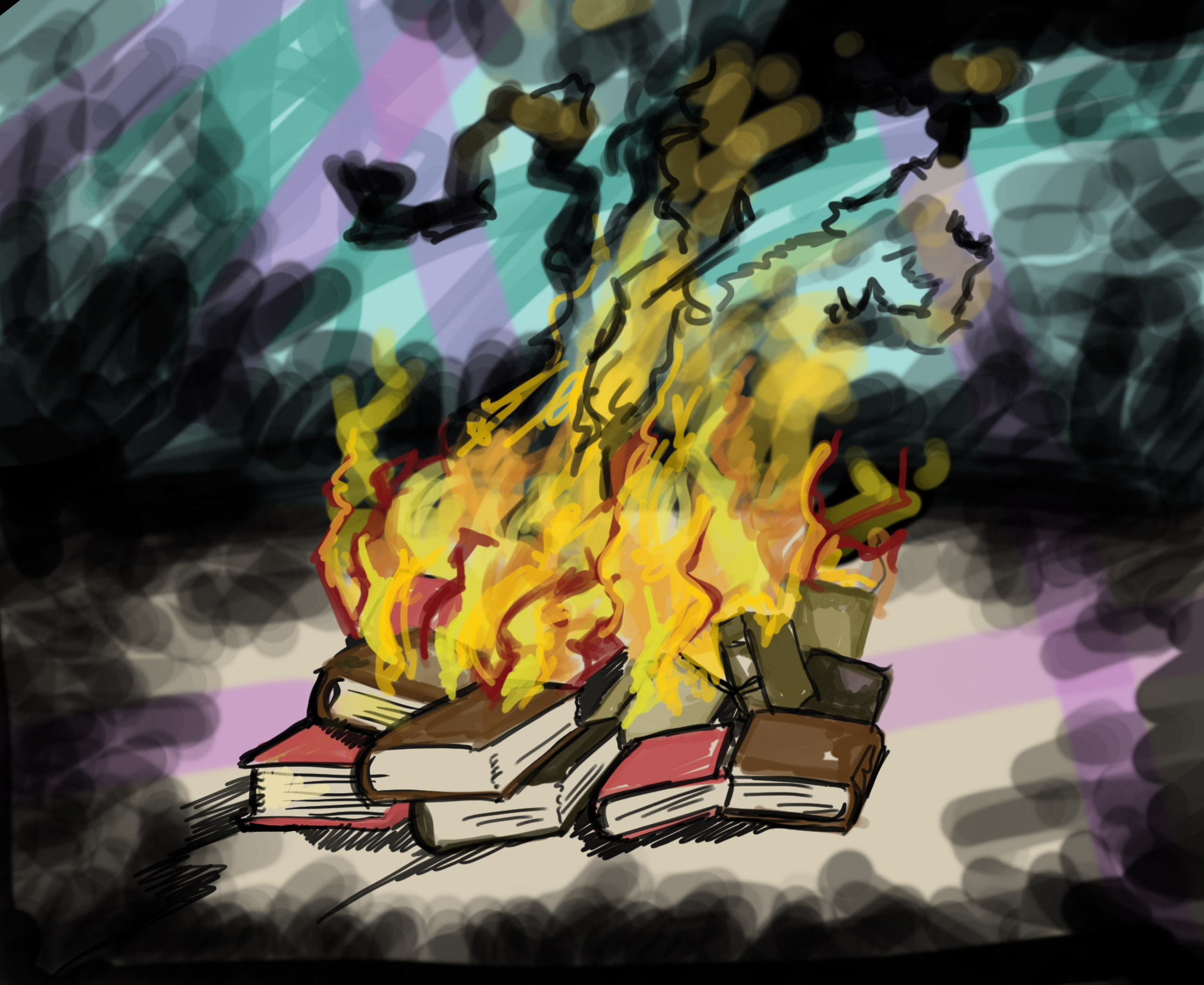

Pulitzer and Nobel-Prize-winner John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath was publicly burned and banned from schools and libraries just months after it was released in 1939. In the 80s and 90s, other complaints were filed; the bestseller’s detractors cited sexual references for their dissent.

Perhaps the most graphic scene occurs when a woman who has just had a stillbirth comes across a dying man in a barn and offers her breast for him to drink her milk. This passage is significant to the novel’s context, as numerous families were starving during the Great Depression.

Some schools in North Carolina have, in the past, banned Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison’s iconic 1952 novel. Invisible Man takes place primarily in New York City, as the African-American narrator attempts to navigate around the racist and discriminatory forces content to keep him running.

The first chapter of the novel was published in a magazine in 1948. The publisher censored a suggestive sequence in which the narrator is aroused by the performance of a Caucasian stripper. The original scene is restored in Invisible Man.

The previous bans in several N.C. schools are partly due to a parent’s complaint about the novel being “filth.” One sexually explicit scene involves a man describing waking up from a dream to his daughter having sex with him while his wife is sleeping beside him.

The erotic Lolita was banned in Canada. Vladimir Nabokov’s narrator has a sexual obsession with the 14-year-old “nymphet” Lolita, an “incarnation” of his lover Annabel, who died when Humbert and she were both Lolita’s age. The narrative may be most disturbing because the reader is stuck in the tainted and deranged perspective of the unreliable narrator, middle-aged Humbert, who claims Lolita first seduced him – and Lolita’s perception is not provided. The narrator’s ceaseless passion presented in constant sexual diction is transfixing: “Naked [ . . . ] spread-eagled on the bed [ . . . ] presented to me its pale breastbuds; in the rosy lamplight, a little pubic floss glistened on its plump hillock.”

The novel was banned from entering the United Kingdom, as well as France—for two years—and was labelled “sheer unrestrained pornography.” The controversy stemmed from its identification of Humbert as a rapist.

Even so, the novel earned a fourth spot on Modern Library’s 1998 list of the Greatest English-language novels of the 20th century.

Tampa, a novel likened to Lolita, was released this summer and is already banned in Australian bookstores. It is about a female teacher who has sex with her 14-year-old male student. Author Alissa Nutting chose to be as explicit as possible; critics have described it as “disgusting.”

Last year, a Michigan school district attempted to ban the ever-challenged Beloved, Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer-Prize-winner. This year, a mother in Virginia unsuccessfully campaigned to remove the novel from her county, citing its references to molestation and rape. For Nobel-Prize-winner Morrison, approaching 1800s slavery comes with scenes of male sexual assault in prison and of bestiality. On the 10th page, the novel reads, “they were young and so sick with the absence of women they had taken to calves.”

Dana Medoro, associate professor of American literature at the University of Manitoba, says of Morrison’s novel, “all the scenes of sexual violence are part of the history her book tries to mourn or represent about the institution of slavery [ . . . ][Slavery] was also about rape and sexualized brutality and being psychically shattered.” In relation to bestiality, Medoro notes that Beloved “explores the treatment of African-Americans as livestock and as consumable bodies.”

White Oleander—Janet Fitch’s 1999 masterpiece—is a sober account of a girl’s experiences in various foster homes after her mother is jailed for murder. The novel has a number of sexually explicit scenes—including one in which Astrid performs oral sex on a teen boy in exchange for pot while babysitting—but nothing as notable as the sexual intimacy between 14-year-old Astrid and foster dad Ray.

“Then he was kneeling in front of me, his arms around my hips, kissing my belly, my thighs, his hand on my bare bottom, fingers in the silky wetness between my legs, tasting me there. My smell on his mouth as I knelt down with him, ran my hands over his body, opened his clothes, felt for him, hard, larger than I thought it would be.”

At my elementary school library, this novel was marked with an “X” on its spine, meaning my classmates and I had to get special permission to take the book out. A similar process now occurs at a school library in Alabama, as a result of a parent’s complaint in 2006 partly in regards to its sexual content. The school decided not to ban the book altogether, because its “message of a brave young girl conquering difficult circumstances was an inspiration for children.” The book is on a “don’t read” list for Texas prisons, though.

Some parents protesting the accessibility of various books in schools have declared their children’s resulting nightmares as reasonable grounds for bans. Regardless of the shock evoked and “obscene” nature portrayed in these texts, these works have a necessary literary and historical role to play.