Katerina Tefft, staff

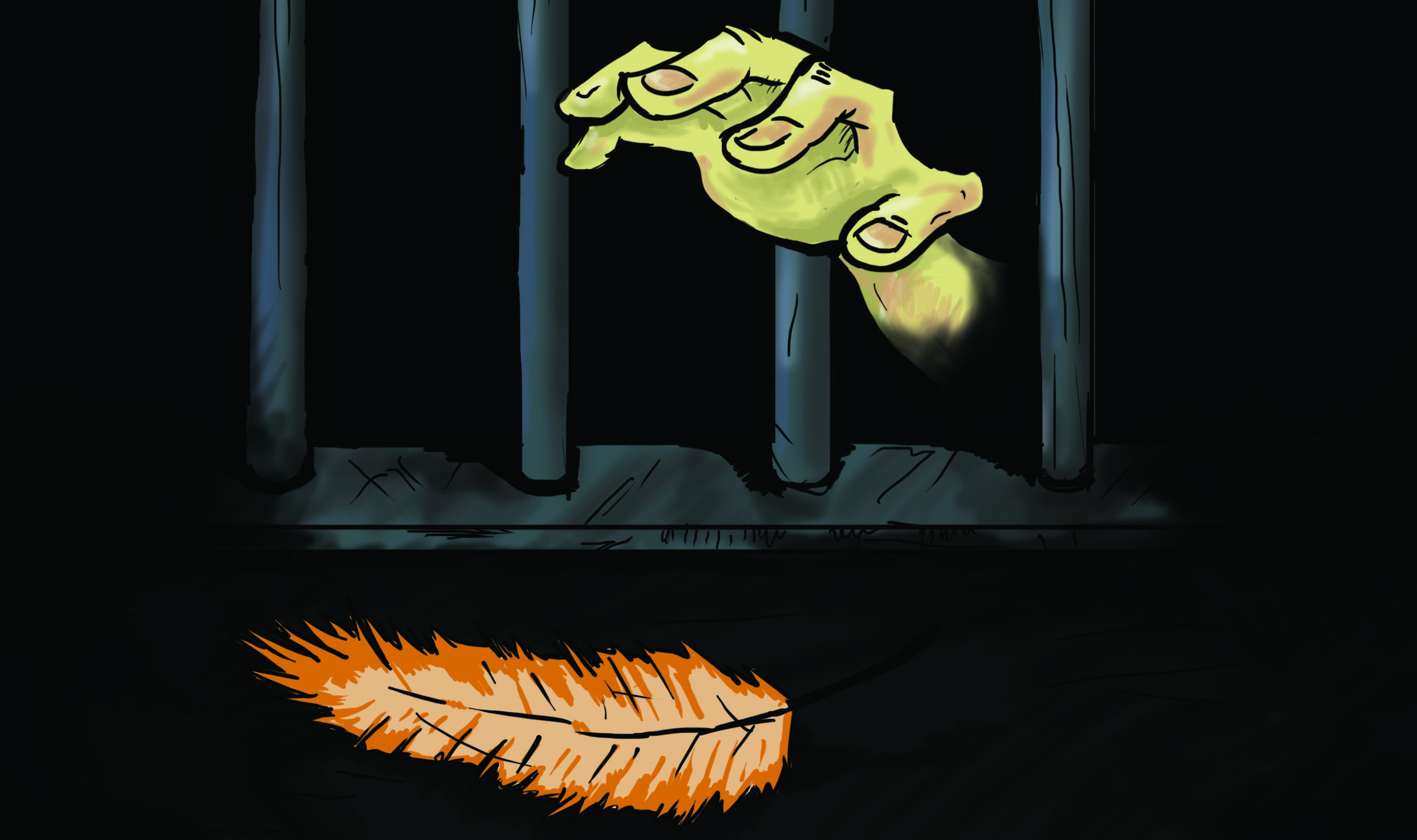

The relationship between Aboriginal people and the Canadian criminal justice system is broken, and evidence is mounting that a radical change is necessary.

An October 2012 report by Canada’s Office of the Correctional Investigator found that Aboriginal people constitute only four per cent of the Canadian population but 23 per cent of the federal prison inmate population, and that the population of Aboriginal people incarcerated in Canada has increased by 40 per cent between 2001-2002 and 2010-2011. The report also found that Aboriginal people are sentenced to longer terms, spend more time in maximum security or segregation, are less likely to be granted parole, and are more likely to have their parole revoked. Correctional Investigator Howard Sapers concluded that these inequalities amount to “systemic discrimination.”

Furthermore, according to the findings of the 1991 Aboriginal Justice Inquiry, Aboriginal people, if convicted, were greater than 2.5 times more likely than non-Aboriginal people to be sentenced to some form of incarceration; this rate is considerably higher for Aboriginal women. It was also found that Aboriginal people on average faced 25 per cent more charges than non-Aboriginal people, and that Aboriginal people had only a 21 per cent chance of being granted bail compared with 56 per cent for non-Aboriginal people.

Alarmingly, Aboriginal women, who make up only four per cent of the Canadian female population, constitute 34 per cent of the female federal inmate population. The number of female Aboriginal inmates has increased by 86.4 per cent in the last 10 years.

Unfortunately, the Harper government seems disinterested in rectifying the situation. Not only did the correctional investigator’s report find “no new significant investments at the community level for federal aboriginal initiatives,” but Sapers has said that the government’s response to his report has been to either disagree with every recommendation or simply reinforce what the correctional service is already doing.

This is hardly surprising; the Harper Conservatives have done much to regress the Canadian justice system. Their 2012 omnibus crime bill, Bill C-10—which imposes mandatory minimum sentences—is expected to carry a price tag of $19 billion. In 2011, the Harper government announced it would spend $158 million on prison expansion in four provinces, and $2 billion over the next five years to take in an estimated 4,000 new inmates. Furthermore, a recent report by Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office found that between 2002 and 2012, justice spending increased by 23 per cent, while crime rates have simultaneously fallen that same amount.

Many Aboriginal organizations have spoken out against Harper’s policies and Bill C-10, such as the Ontario Federation of Indian Friendship Centres, which wrote to the prime minister, “It will be Aboriginal offenders, those most disproportionately represented in prisons and at every stage of the justice system in Canada, who will be most affected by this draconian legislation.” The Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund also wrote, “Through its [ . . . ] ‘one size fits all’ approach to sentencing, Bill C-10 adopts a formalistic approach to equality that will serve to perpetuate the historic disadvantage of marginalized groups.”

Harper is sinking billions into prisons instead of social programming, while one in four Aboriginal children in Canada live below the poverty line. Locking up minor drug offenders will not close the 28.8 per cent income gap between Aboriginal people and other Canadians; it will only perpetuate the well-documented cycle of crime and poverty. In fact, investing in health and education instead of incarceration would benefit not only Aboriginal people but the Canadian economy as well.

For example, each inmate in the correctional system costs the federal government approximately $110,000 per year, while one year of supervised release costs only $30,000. Furthermore, according to the National Council of Welfare, the increase in market output if educational and labour standards for Aboriginal people matched other Canadians by 2026 would be $36.5 billion. The reduction in government expenditures if these outcomes were achieved would be an additional $14.2 billion.

Clearly the mainstream justice system is failing Aboriginal people, and the situation has reached a breaking point. The solution is a radical one: a return to traditional Aboriginal restorative justice, but only in the context of Aboriginal self-government.

A 2010 Environics Institute study found that more than half of urban Aboriginal people had little or no confidence in the justice system and were more than twice as likely as the general Canadian population to feel this way. Clearly, the system lacks legitimacy in the eyes of Aboriginal people, and it is not hard to understand why.

Firstly, their relationship to the Canadian state is complicated by a history of genocide and colonialism. Prior to colonization, Aboriginal peoples were autonomous and self-governed. They had no prisons, yet had fully functioning societies for thousands of years. The western European model of criminal justice was forcibly imposed upon them, as was the Canadian state itself. Secondly, the western European model, with its focus on punishment, isolation, and individualism, is totally incompatible with traditional Aboriginal values of non-hierarchy, community, healing, and interdependence.

Restorative justice, the alternative to incarceration, can take many forms, including community sentencing circles, victim-offender mediation, community service, sweats and other cultural activities, counselling, healing circles, essays written for self-reflection, restitution, formal apologies, and drug and alcohol rehabilitation.

Restorative justice differs significantly from the current Canadian system in that it focuses on addressing the root cause of the crime, allowing the offender to take responsibility for his or her own actions, repairing the damage done by the crime, and allowing everyone affected by the crime to heal. Rather than rely on professionals and authority figures, it places responsibility for solving the conflict in the hands of those parties directly involved in and affected by the crime. It also focuses on strengthening the offender’s personal relationships, rather than isolating them from loved ones.

However, restorative justice can only truly reflect Aboriginal traditions in the context of self-government. The small changes made to the Canadian justice system thus far to make it more inclusive to Aboriginal practices are problematic because their purpose is only to make the existing system more efficient, as opposed to addressing the question of its very legitimacy.

These so-called restorative justice initiatives erode Aboriginal traditions by taking them out of their intended context and placing them within a western European system that is based on totally incompatible values. The traditions that are left are fragmentary and watered down, further whitewashing Aboriginal identity. Moreover, they attempt to appease Aboriginal people by giving the illusion that the system is culturally appropriate and non-oppressive, while hijacking their traditions and spirituality.

This surface indigenization also damages Aboriginal communities. As researcher Jessie Sutherland writes, it “co-opts First Nations leaders and community members into believing they are contributing to significant cultural renewal and self-determination. However, in administering Canadian law they become ‘agency Indians’ for the Canadian state.” For example, the traditional role of elders in Aboriginal communities has been that of teachers and healers, but under the indigenized Canadian justice system, they have become more like judges who aid in sentencing. This turns traditional non-hierarchical Aboriginal justice on its head, and insidiously enforces western European values of hierarchy and authoritarianism in Aboriginal communities.

The goal, therefore, of Aboriginal justice reform must be self-government and a return to true restorative justice. Only this can correct the systemic discrimination that Aboriginal people face in the Canadian criminal justice system.

Katerina Tefft will be presenting on the topic of Aboriginal justice at the Whose Winnipeg? Neoliberalism, Settler Colonialism, and the Production of Urban Space workshop on August 20th. Visit http://opencuny.org/whosewinnipeg2013/ for details.

Excellent article. I shall pass this onto the UN Special Rapporteur for Indigenous Rights. He is visiting Canada in October and has asked for people to write to him about these matters.

http://unsr.jamesanaya.org/visit-to-canada/united-nations-special-rapporteur-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples-to-carry-out-official-visit-to-canada-from-12-to-20-october-2013