A recent study from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Stockholm University, and University College London has shined some light on the relationship between socioeconomic position and fertility rates. Published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences on Aug. 29, the study aims to describe “demographic transition” in today’s modern post-industrial society. The findings claim that as people become wealthier, they tend to live longer and have fewer children.

Researchers used data from the “Uppsala Multigenerational Birth Cohort Study (UBCoS), a unique Swedish dataset that tracks 14,000 individuals born in the early 1900s and all their descendents to the present day.” The study was able to show that having a high parental socioeconomic position (SEP) and low parental fertility increases the descendant’s SEP over generations. However, the researchers’ findings also disproved the notion that high parental SEP and low parental fertility increases the descendant’s own reproductive success across generations.

That is to say, although descendents tended to have greater income and more exposure to higher education than their parents or grandparents did, they did not then experience reproductive advantages (higher fertility) than their older generations. They, in fact, averaged less children than the generations which preceded them.

The study analyzed datasets using the evolutionary selection strategies of “r/K selection theory.” The theory explains how, depending on certain variables, an organism may opt to produce more or less offspring. For stable environments with a constant population size, “K-selection,” where less offspring are produced, is favoured. In “K-selection,” parents devote more energy to rearing only a few offspring into maturity; humans are an example of a “K-selected” species. For unstable environments where there may be a real or perceived higher infant mortality rate, “r-selection” is preferred: many offspring are produced with the expectations that few will survive. Because of the higher number of offspring, parents invest little energy raising them. The population grows fast and dies even faster, but some survive to the point of maturity.

“Demographic transition,” then, is a model that describes population growth rates and how they change over time.

For the study in question, researchers noted that the demographic transition could be explained by a shift observed between r-selection and K-selection over the generations in the sample population.

The sample utilized in the study consisted of all live births, which occurred at the Uppsala University Hospital in Sweden between 1915 and 1929, provided by the Uppsala Multigenerational Birth Cohort study (UBCoS). The data tracked approximately 14,000 individuals born at the hospital and all of their descendants across four generations with a cut-off year of 2009. The sample was also deemed a fair representation of both Sweden’s infant mortality rate (two per 1,000 live births in 2009) and fertility rate (1.9 births per woman in 2009).

Compared with similar studies, Anne Goodman, Professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the first author of the published study, stated that “previous studies of modern populations have used smaller and potentially biased samples.”

According to Goodman et al., past studies have used samples of men at military services stations, US military personnel and German physicians as their sample groups with data across only two generations of lineages, compared to four generations in the current study. Although these past studies are perhaps more limited in scope or less reliable due to the nature of their sample groups, the study by Goodman et al. was able to replicate many of the same findings.

Researchers defined “socioeconomic position” (SEP) as “an individual’s or group’s position within a hierarchical social structure.” SEP being dependant on a combination of variables—occupation, wealth, education—researchers combed through such indicators of SEP as school marks, enrolment in university, as well as disposable family income as measures of the sample groups’ SEP. Reproductive success of each generation was measured with three direct indicators: survival to age 16, mating success and marriage before the age of 40, and fertility (number of children up to 2009).

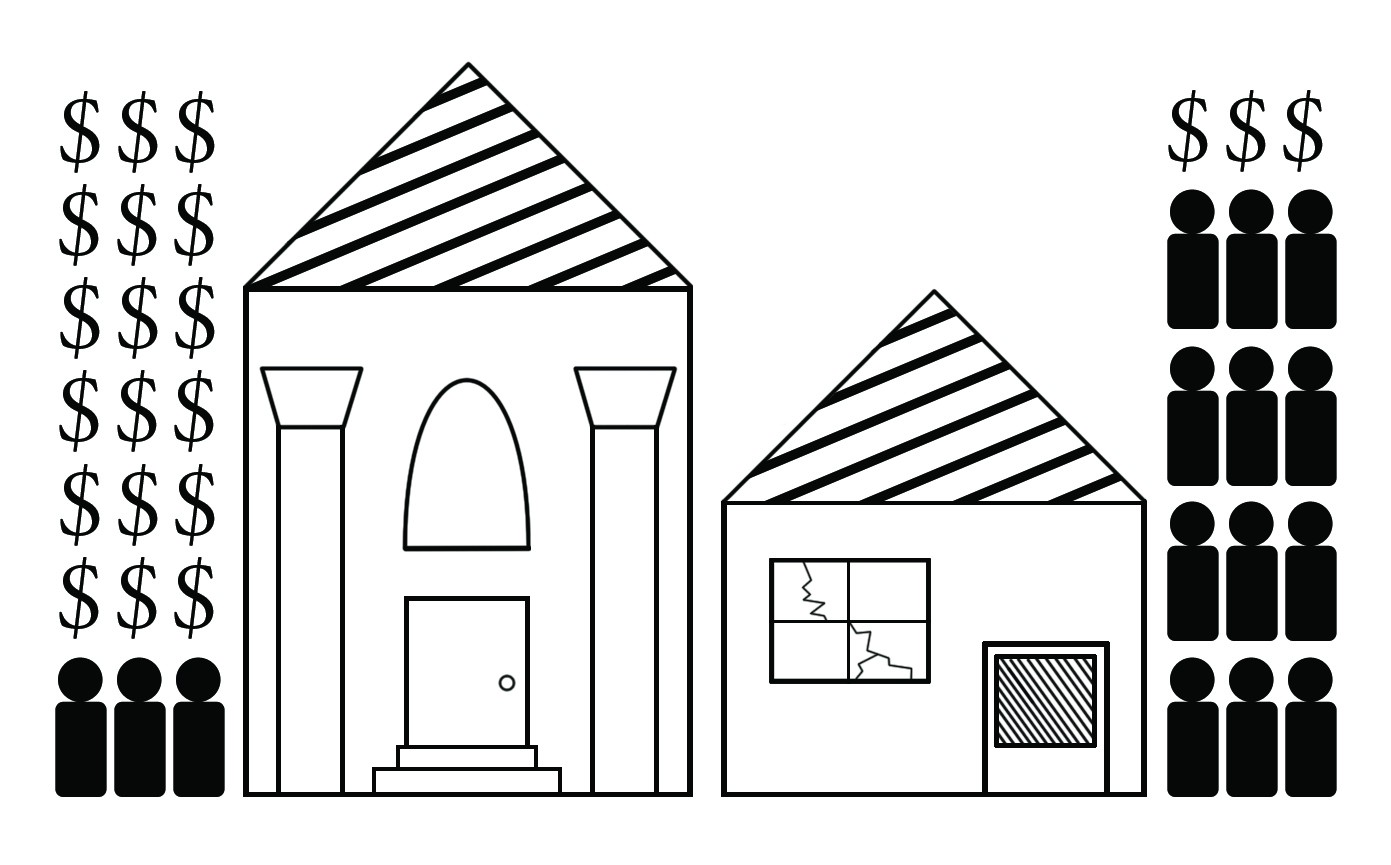

The study was able to show statistically that the average fertility for each successive generation declined, while the cohort’s socioeconomic position rose, providing strong evidence for the prediction that fertility limitation enhanced descendant SEP. And the opposite was also true: the lower the rung a family occupied on the socioeconomic ladder, the more children they had in relation to those wealthier families of society.

The subtly troubling implication is, in the authors’ own words, that their “findings highlight that differences in fertility and SEP can have important long-term effects on the persistence of social inequalities across generations.”