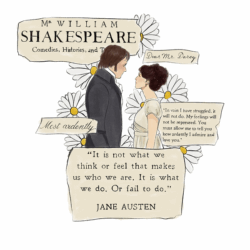

Erin Weinberg, an instructor II in the U of M department of English, theatre, film and media, spends her days exploring how stories from different eras reveal enduring questions about language, power and identity. Her work bridges classic texts by authors like William Shakespeare and Jane Austen with broader conversations that continue to shape how we understand the world today.

“I’m a Renaissance drama scholar by training, and my secondary research field is Jane Austen,” Weinberg said. “Lucky me, I get to read all the time!”

Weinberg’s academic journey reflects both curiosity and range. According to her, being an instructor allows her to explore a variety of interests from early modern theatre to crime fiction. “I pursue anything related to English literature that interests me,” she said. “Sometimes it’s Shakespeare, sometimes it’s Austen,” she added.

Her recent conference paper focused on “Jane Austen and engagements,” which argued the period between engagement and marriage is a time of instability rather than triumph. Weinberg argued that Austen’s heroines often find themselves in a vulnerable position during this liminal phase, when their futures are still uncertain.

Weinberg’s work often returns to questions of power. “My research, as well as my teaching, tends to circle back to power dynamics,” she said. “Who has power, who wants power and what a person or group is willing to do to achieve that power.” Her work also focuses on how wealth, class, gender and ability influence who holds power, why certain voices carry more weight and the challenges of speaking truth to that power.

Beyond Austen and Shakespeare, Weinberg’s research also engages with how language can be used as a tool of control. She studies memoirs by people who have escaped cults and coercive groups, analyzing how leaders manipulate meaning to maintain dominance. “While words don’t have any physical dimension, the value systems behind [them] can be more restrictive than handcuffs or an electric fence,” she said. “Cult leaders redefine words in order to control members, and a significant part of deconstruction from a cult […] is redefining those words outside the context of damnation.”

Weinberg’s fascination with language extends into the classroom. Earlier this year, she caught international attention after a tweet about using Taylor Swift’s album The Tortured Poets Department to teach grammar went viral, earning her an interview with The New York Times. “Is it a department of tortured poets or for tortured poets?” she asked. “This was a great opportunity to use current events as a teachable moment.”

Her teaching philosophy, like her research, emphasizes connection and creativity. She often encourages students to see literature as something that reflects lived experience. In her “Literature and Food” course, Weinberg uses food as a lens for exploring themes of community, identity and survival. “Food isn’t just the stuff that we consume — it’s a symbol of community and identity,” she explained. As a member of the Food Matters Research Cluster at the U of M Institute for the Humanities, Weinberg collaborates with scholars across disciplines to explore how food connects people and ideas. “It’s immensely inspiring,” she said. “I can’t tell you what a joy it is to spend time eating with other food lovers from across disciplines!”

Looking ahead, Weinberg is studying how victims are portrayed in Agatha Christie’s The Body in the Library. She is examining how language and perspective can shift sympathy away from the victim to other characters. Her approach of blending close reading with questions of ethics and voice demonstrates her belief that “words have power” and literature is never just about words on a page.

Special note from Erin Weinberg — “I’d like to remember Dr. Refaat Alareer. He was a university professor at the Islamic University of Gaza and a fellow scholar of Renaissance literature. The Israeli Occupation Forces demolished his entire university on Oct. 10, 2023. They targeted Dr. Alareer and bombed the building where he was sheltering, killing him, his siblings and his siblings’ children. Dr. Alareer spent his life harnessing the power of words to maintain hope, and the targeted nature of his murder and the demolition of his entire university shows just how powerful words, verse and education can be.”