Few television shows right now feel as sharp and addictive as The Diplomat. With the arrival of its third season, the series continues to deepen its intricate depiction of international affairs and personal drama.

At its heart is Keri Russell’s commanding performance as Kate Wyler, the American ambassador to the U.K. Wyler’s quick-yet-informed navigation of challenges brings the messy realities of diplomacy to life, making the high-stakes world she lives in both intimate and authentic. It is no surprise the show has earned praise for its writing and pacing, and I have admiration for how it showcases the complexities and contradictions of women’s leadership on the world stage.

Yet, as much as The Diplomat excels in portraying its female leads as complicated and compelling, it also falls into a common narrative trap. At the beginning of this most recent season, Allison Janney’s character, Grace Penn, is sworn in as president after the sudden death of the previous president — a scenario echoed in many other political dramas. Consider Claire Hale Underwood in House of Cards, who gains the presidency after her husband resigns, or Selina Meyer in Veep, whose first term is the result of the sitting president’s resignation. Time after time, these shows seem comfortable with women leading only when they step into the role through extraordinary circumstances, rather than winning through hard-fought campaigns.

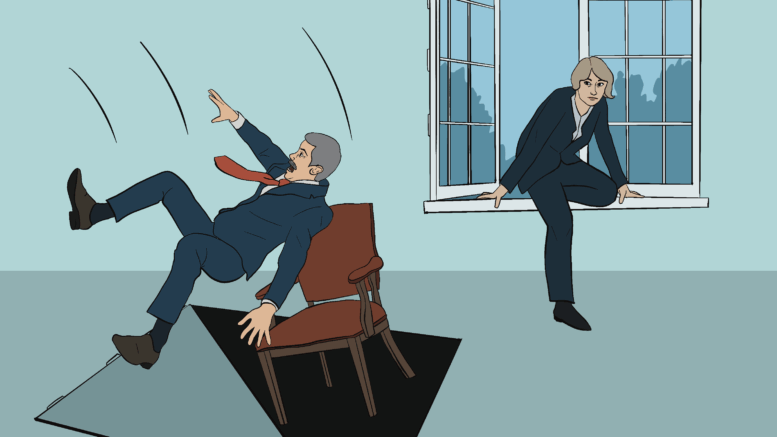

The moments following the president’s passing in The Diplomat illustrate the chaos surrounding Penn’s new reality. At the time, she is overseas and must be abruptly sworn in at the U.S embassy in London, right in the building’s lobby. She is sworn in wearing a running shirt under her blazer, as there is no time to find appropriate attire. This episode highlights how unplanned, hectic and crisis-driven her rise to power is, leaving her with little agency to claim the presidency on her own terms.

It is striking how rarely a woman wins her way into the highest office onscreen, but this problem extends far beyond fictional television. In Canada, Kim Campbell’s short term as prime minister followed the political wreckage left by Brian Mulroney. Campbell, who became Canada’s first and only female prime minister in 1993, inherited the leadership of the Progressive Conservative party just months before a federal election. The Mulroney government was deeply unpopular at the time, due to a recession, high unemployment and failed constitutional reform.

When Campbell took over, her party was facing collapse. She was not chosen by voters to lead and was tasked with saving the party from being voted out of existence. In the 1993 federal election, the Progressive Conservatives suffered a historic defeat, winning only two seats and ending Campbell’s time as prime minister after less than five months in office.

This is a familiar situation for many women who step into leadership at the most challenging moments, being expected to move mountains when the odds are already stacked against them. Since then, no major federal party in Canada, except for the Greens, has had a woman lead them into a general election.

The persistence of this trope, onscreen and in real life, speaks to the limits of our collective political imagination. Even when female characters hold on to power after gaining it through unusual circumstances, their

paths are rarely depicted as straightforward or fully legitimate. The emphasis remains on exceptionalism, rather than normalizing women as political victors from the start. It may be time, both on television and in real life, to envision a world where women win and lead on their own terms — not simply as caretakers in moments of crisis, but as architects of their own success.