One of my fellow international classmates said to me at the very beginning of our first term, “I

don’t think I belong here.” This is not an uncommon feeling among international students. I

believe most people, if not every person, who moves far from home in pursuit of higher studies

shares a similar mindset. They often undervalue their worth and feel the need to compensate

with hard work, often not to prove something to others, but to prove to themselves that they

belong, that they have earned this opportunity fair and square.

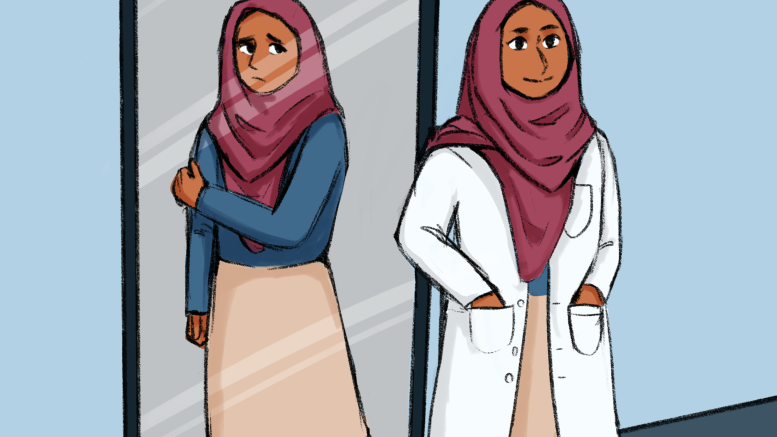

For many international students globally, including at the U of M, excelling academically is not

the only challenge. Quietly, many battle imposter syndrome — feeling undeserving of their place

despite clear achievements. People who are Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC)

and work or study in predominantly White environments wrestle with imposter feelings at higher

rates, noted Kevin Cokley, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor.

Imposter syndrome describes the psychological experience of doubting one’s abilities, even in

the face of success. It can manifest as the fear of being “found out” as being less capable than

peers. While this feeling is not unique to international students, it can often be intensified by the

realities of studying in a new country.

International students at the U of M may navigate multiple layers of adjustment, such as

adapting to new academic expectations, communicating in a second language and living far

from family and support networks. On top of these struggles, Winnipeg’s extreme cold weather

and financial pressures silently add to the weight of expectations. These factors make moments

of anxiety and self-doubt more acute.

In this context, a strong sense of belonging is more than comfort — it is essential. Students who

feel connected to peers, faculty and campus life are better equipped to manage imposter

syndrome. A sense of belonging provides reassurance that self-doubt is temporary and normal,

rather than evidence of failure. Without this support, international students may feel isolated,

impacting both well-being and academic performance.

At the U of M, this issue is especially relevant. Winnipeg can be an isolating environment for

those unfamiliar with harsh winters. Another contributing factor might be the smaller

international student population in Winnipeg compared to larger cities. Although the community

is diverse, international students often find themselves outside of campus conversations, unsure

of where they fit in. Imposter syndrome matters because it affects more than confidence. It

influences how students participate in classrooms, how often they seek support and whether

they see themselves as capable of success. If this insecurity is left unaddressed, it can impact

students’ mental health, reduce engagement and even push them to leave programs early.

Universities often address international student needs through tutoring or bursaries. Despite

being valuable, these resources cannot replace the cultural and emotional support that a sense

of belonging provides. Building belonging means creating safe spaces for students to share

struggles, expanding mentorship programs and training faculty to acknowledge and validate

impostor syndrome.

At the U of M, many such supports are available for international students (see QR code). When

students feel they truly belong, they stop questioning their place and see themselves as part of

a community.