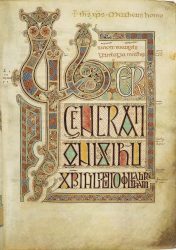

Folio 27r from the Lindisfarne Gospels.

I have always been captivated by the opening titles of classic Disney films like The Sword in the Stone and Sleeping Beauty. The story begins in a bedazzled fairy tale book with gothic lettering and colourful illustrations. This art style never fails to evoke a whimsical world of dragons and wizards, but did you know that it has roots in a sacred tradition that is almost 1,500 years old?

In his book Illuminated Manuscripts, writer and historian Richard Hayman explains that illuminated manuscripts are handwritten texts that are decorated with gold, silver or other rich colours to bring light to the pages. These manuscripts were once popular in medieval Europe before the invention of the printing press, but they remain some of the finest works of art from the Middle Ages.

According to Hayman, manuscripts are made of vellum, or cleaned animal skin, folded together to make quires. The scribe writes on the vellum using black or brown ink from soot or oak gall, then the illuminator applies pigments and gold leaf to the pages. Finally, the pages are bound in leather or fabric and sometimes decorated with enamel, jewels, and ivory.

Most of the early medieval manuscripts are religious texts and would have been produced by monks to celebrate and reaffirm Christian messages. One famous example is the Book of Kells, an 8th century manuscript of the Gospels created by Celtic monks in Iona, Scotland before it was brought to Ireland to escape Viking raids. The book is decorated with interlace motifs as well as illustrations of animals that symbolize evil or Christ’s resurrection.

However, Hayman writes that by the 13th century, the production of manuscripts began to shift away from monasteries to the public — royalty, wealthy aristocrats and even laypeople started to commission artisans to produce books of hours, a type of prayer book, in great quantities. Secular works on fictional beasts and mythical characters such as King Arthur also emerged.

Hayman argues that due to this shift, amusing and mischievous illustrations became more common in book margins. For example, drawings of axe-wielding rabbits and knights fighting snails started to appear, though many of the symbolisms of these strange creatures are long lost to the sands of time.

While these ornate works of art may seem distant and exotic to Winnipeggers, U of M archives house several notable historical texts from this period. For example, the Rare Book Collections on campus contain Pomianyk of Horodyshche, one of the oldest Cyrillic manuscripts in North America dating from the 15th century, as well as a 1438 printed edition of the Latin Bible.

Illuminated manuscripts continue to bridge the sacred to the secular and bring whimsy to our lives centuries after their creation. The next time you revisit your favourite fairy tale or gaze upon the university libraries’ rare books, know that you might well be looking at the echoes of a medieval hand, gilding pages with light.