The increased global acceptance of right-wing political parties and conservative ideology has gained much attention in the past few years. The deteriorating effects on the public sphere of governments that prioritize the interests of dominant religious groups, conservative ideologies and the free market are boundless.

While this has been a topic of discussion for quite some time, considering the scheduled general elections in many countries in the near future, a conversation about populist politics is necessary.

While Canada’s current government is an exception to this surge of further-right regimes — not that there’s nothing to be said about the Liberal party — many other countries globally have seen growing support for distrustful right-wing politics.

Our neighbour to the south, the U.S., is still recovering from the actions of its former president, Donald Trump, who said the coronavirus would die in sunlight. COVID-19 and the Trump administration’s response is just one example. The incumbent Democrat president, Joe Biden, has not yet called for a ceasefire in Gaza despite the humanitarian crisis in Palestine having become extremely dire.

Giorgia Meloni, who was elected prime minister of Italy in 2022, and her party, Brothers of Italy, represent the most far-right government Italy has seen since Benito Mussolini.

The U.K.’s conservative prime minister Rishi Sunak got into power after a complicated Tory power struggle in 2022. He has expressed deeply conservative beliefs about trans people and even immigration, despite being the descendant of an immigrant himself. The country has not seen a Labour prime minister since Gordon Brown in the late ’00s.

Far-right leaders are in power around the world, including Argentina’s president, Javier Milei, Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi. India has seen 10 years of right-wing extremist governance, and chances are, with the 2024 general election, the trend is going to continue, plunging the country into nationalist and religious fundamentalist despair.

This global trend certainly raises concerns about the popularity of religious conservatism, increased racial and gender injustices, the acceptance of inequality as part of the competition in market economics, and the relationship between capitalism and the state.

Democratic systems of governance acknowledge that everyone deserves to influence government, unlike governments that favour capitalism, encouraging private entities in the market to drive the social sphere by themselves.

When capitalism reigns, political rights are granted based on capital ownership. In its extractive logic, the only citizens who matter are those who own capital. When the state promotes capitalism those who own more capital are allowed to exercise power.

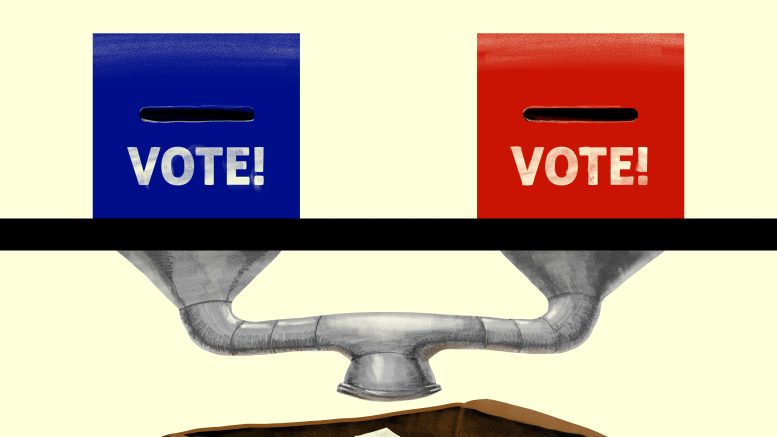

The reasons this trend exists are numerous and complicated, but it’s more important to think about how we should combat it — voting.

I know that free health care, cancelled student debts and the need for equal rights for all races and genders will all remain our needs — even if these right-wing governments are magically voted out globally — because the capitalist system requires these inequalities to stay in place.

Capitalism’s need for inequality is easily discernible in our society. It maintains scarcity because the job market requires unemployment, the housing market requires homelessness and so on. Scarcity is also justified by the argument that it increases innovation, competition and motivation. This is not only untrue, but it is also an ableist and unjust approach.

Since the alternative to this far-right governance is usually lesser evil replacement candidates that don’t challenge the capitalistic status quo, there is no hope for systemic change.It is also true that as long as governments are influenced by capitalist ideology, there cannot be a system that supports the socialist revolution.

There are so many flaws associated with electoral systems globally — big money financing campaigns, voter suppression, buying out votes, corruption and many more. I’m aware that all these arguments exist and are valid, but I still think that voting can help.

All this might sound surprising coming from a class reductionist — yes, reader, I have accepted that title — but one Marxist understanding of elections is less anti-voting than many are assuming. In fact, the idea is to bring a working-class majority representation in the legislature, thereby achieving a transfer of power.

I certainly don’t consider voting a solution for all the issues in the world. Especially considering that the oppositional candidates globally resemble the U.S.’s Trump and Biden situation. There is a general disapproval for this option, and the question “how did we end up with them again” is gaining popularity. However, voting is probably the only hope left for us since the humanitarian crises in many countries are actively and deeply affecting us all.

I don’t think a tectonic shift in the economic and political order is happening anytime soon.

So, in the meantime, I’m going to vote for anyone who is not going to support Modi. I’ll hope that the people I love and care about get to live without fearing a majoritarian government imposing capitalist and religious fundamentalist values onto them.