One in four Canadians is possibly affected by liver disease. Often, those with liver disease are unaware of it until the disease reaches an advanced stage.

Robin da Silva is an assistant professor in the U of M’s Max Rady college of medicine. The da Silva lab researches the development of fibrosis, scarring of the liver, during liver disease.

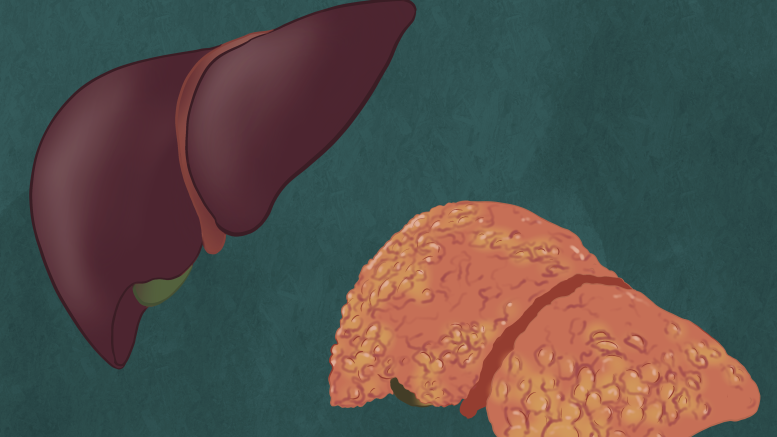

The most common type of liver disease is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), an accumulation of fat unrelated to alcohol use.

“That’s a very broad disease, where you have fat in the liver and some what we call elevated liver enzymes,” da Silva said. “A lot of people have that, and many people don’t know that they have that.”

NAFLD is often seen in patients with metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a group of health conditions including high blood pressure and sugar, excess body fat carried at the waist and abnormal cholesterol levels. The syndrome affects up to one third of adults in the United States and increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, Type 2 diabetes and liver disease.

Though NAFLD may be mild and not present any symptoms, about 10 to 15 per cent of people with the condition will develop non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Characterized by excess fat deposits and inflammation, NASH can cause liver damage similar to that experienced by alcoholics, even among those who do not drink.

Minor liver damage can be repaired by the body. However, the deterioration associated with NASH may be too severe. Fibrosis is a process that occurs when scar tissue replaces damaged liver tissue.

“When the immune system is trying to do its work, if there’s inflammation, this inflammation stimulates more immune activity,” da Silva said. “Those immune cells basically generate fibres in the liver. That’s a normal process that does happen normally whenever you’re turning over tissue, but the problem is when that becomes disordered, and it accumulates.”

Almost no therapies exist to treat fibrosis. In patients who are obese, losing body weight can help reduce the amount of fibrosis in their liver. Even then, da Silva said that this approach is often unsustainable, as weight loss is difficult, and many people eventually return to their previous body weight.

Certain drugs used in diabetes inhibit appetite, which may be beneficial in treating fibrosis as it causes weight loss. However, this has not been studied within the context of fibrosis.

“There’s some new things happening, but this is kind of skirting the issue,” he said. “It’s getting at it from the other end. It’s not dealing with what the source of the fibrosis is.”

Da Silva’s research focuses on how immune cells are generating fibrosis in the liver. The da Silva lab has found that folate and B12 metabolism influence the behaviour of these immune cells by reducing the severity of liver fibrosis.

For many patients, the battle against liver disease does not end at fibrosis.

“[Patients may go] from NAFLD to NASH,” da Silva said. “And NASH is when you have that inflammation and fibrosis, and when that fibrosis accumulates to a certain extent, it starts to prevent blood flow through the liver, and at that stage, we start to refer to it as cirrhosis.”

Cirrhosis, he explained, is a very serious condition for which there is no treatment. The only options for patients diagnosed with cirrhosis are tissue transplants or the removal of liver tissue. Those diagnosed with compensated cirrhosis typically have a life expectancy between two to 12 years.

According to the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, heavy drinking is consuming at least five drinks per day, on five or more days in a month. A 2019 study found that 20 to 25 per cent of people who drink heavily over a long period of time will develop cirrhosis.

Certain diseases, such as the viral diseases hepatitis A, B and C, may induce fibrosis. Hepatitis C is especially prone to generating fibrosis.

“Newer drugs have been developed that are effective at treating hepatitis C,” da Silva said. “About 10 years ago, that was very difficult to do.”

“Vaccines do a lot for hepatitis,” he added. “We don’t realize it in the same way that we don’t realize how good the vaccines are against mumps, measles and rubella, and the other ones that we get vaccinated against, because we don’t see them anymore.”

Da Silva emphasized that rates of liver disease have continued to rise, noting that “this is a problem that’s becoming a bigger problem.”

“More research is needed for this,” he said. “The big message is, about fibrosis, that there’s no treatment for it. We have treatments for many diseases. We have fantastic medicines. But this is one that we have no treatment for, which is astonishing. And to get those medicines, to develop those medicines, we need more research.”