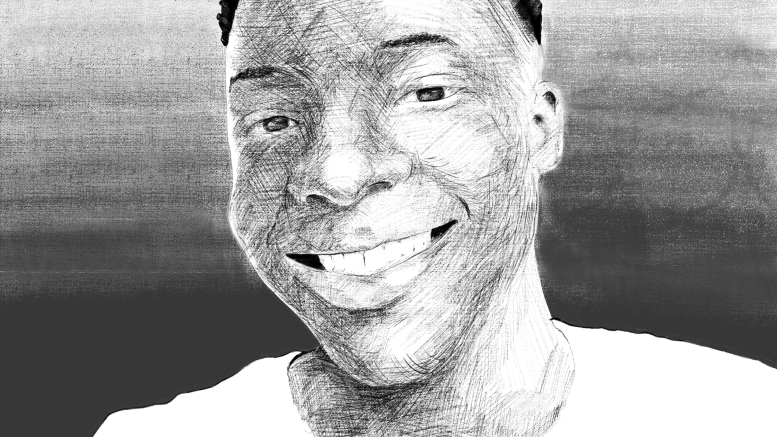

Right at the year’s close, news that 19-year-old U of M international student Afolabi Stephen Opaso was killed by police on Dec. 31, 2023 shook the community. Apparently, though, it didn’t hit the U of M’s administration hard enough to justify a dedicated acknowledgement that one among us had suffered a terrible end.

In the wake of it all — the grief, fear, confusion and justified outrage, the U of M did not send out an email the moment the public was made aware a U of M student was killed. No, a little coverage of Opaso’s death was surreptitiously slotted in between light bulletins almost nine entire days after the fact.

An email signed by vice-provost (students) Laurie Schnarr circulated to students on Jan. 8, 2024 began “Happy 2024 Bisons.”

“Happy” 2024 indeed! Although the new year was marred before it even began when police shot Opaso to death during a mental health crisis. But hey, happy 2024, Bisons!

The email was as tactless as it was overdue, sandwiching a casual statement on Opaso’s death between new year’s greetings and notices about free UMSU breakfasts. Out of all the message’s 841 words — excluding Schnarr’s postnominals — only 72 were spared for Opaso.

This tonal dissonance could have easily been avoided if this message was just a short acknowledgement dedicated to Opaso’s death. Now, at worst, Schnarr’s email reads disingenuously, as if the abrupt end of a student’s life is no more noteworthy than a reminder of daily pedestrian operations like the UM Annual Career Fair.

Worst of all, though, was the way the email seemed to detach Opaso’s death from the cause. His death “marked a very tragic and sad end to 2023,” the email read, with no mention of how he died — the fact that he was shot by Winnipeg police.

Schnarr’s email concluded its little 72-word note with a reminder that “if you or a student close to you is struggling or in crisis, please reach out to one of the many supports and services available to UM students.”

Setting aside the way this language implicitly suggests the U of M has ample and sufficient supports for students — there are “many” of them in case you’re in a crisis, and past making them available the university bears no accountability if your crisis deepens — Opaso’s death was not “tragic” in any sense of the word. Calling this a tragedy paints Opaso’s death as an inevitability to me, as if it was unpreventable, as if he was bound to be killed by police.

It wasn’t a tragedy, it was an injustice. Opaso was in distress and the police approached him as a threat. This should not have happened, it was wrong.

But calling the killing of Opaso anything but a tragedy leads the university into territory that highlights the dangers of its own passivity.

To call his death an “outrage,” for instance, would be to acknowledge that the police had mishandled a distress call, and such an acknowledgement raises some other unsettling questions. For instance, when the university works closely with police, or when police are on campus, isn’t the university knowingly welcoming an entity that could pose threats to students’ lives and safety?

To call Opaso’s death a sign that mental health supports are insufficient would be to acknowledge that insincere performances like hyperlinking student supports in an email are flaccid, placating moves at best. Sharing information that resources exist and calling it a day is too idle for an institution that — let’s be honest — contributes to the deteriorating mental health of so many of us.

The problem is, even if this embarrassing email hadn’t been sent, any death at the hands of police is a political one. Once you layer on the particularities of Opaso’s case, there are a handful of ways his death emblematizes broader systemic issues. To not even acknowledge that doesn’t just look like a silly attempt to keep the university out of hot water, it perpetuates those issues.

One thing shouldn’t be left unsaid: Opaso was Black, and Winnipeg police’s troubling treatment of Black men has been the subject of scrutiny for years. In light of that, the U of M email’s quick and belated treatment of Opaso’s death was racist, passing over the problem of anti-Black racism among police that absolutely needs to be examined more closely.

But if the U of M were to acknowledge Opaso’s death to any substantial degree, it would have to then account for the fact that its students’ fates are intertwined with the university’s operations. In short, the U of M would have to do something besides announcing students can seek out “services.”

The sum total of these slights — the timing, the delivery method, the dearth of detail and the careless non-committal hand-wave that people might be affected by this — is a response more closely resembling some genial Wal-mart greeter checking off a shopper’s receipt than any humane response to the end of a teenager’s life.

Of course, the blame for the U of M’s email probably doesn’t fall squarely on Schnarr’s shoulders, but Schnarr should be ashamed that her name was attached to a message as crass, callous and comically thoughtless as that.

Did the U of M’s email send the message that Black lives matter at all? Did it even show us that any part of the student body is a life worth remembering?