The day Afolabi Stephen Opaso was shot and killed by Winnipeg police, he called Favour Babalola, his friend of eight years, twice.

The two had known each other since high school in Nigeria, and had both come to the University of Manitoba to study. They stuck together through thick and thin. Babalola was there with Opaso through his sporadic mental health crises, and a hospitalization earlier this year.

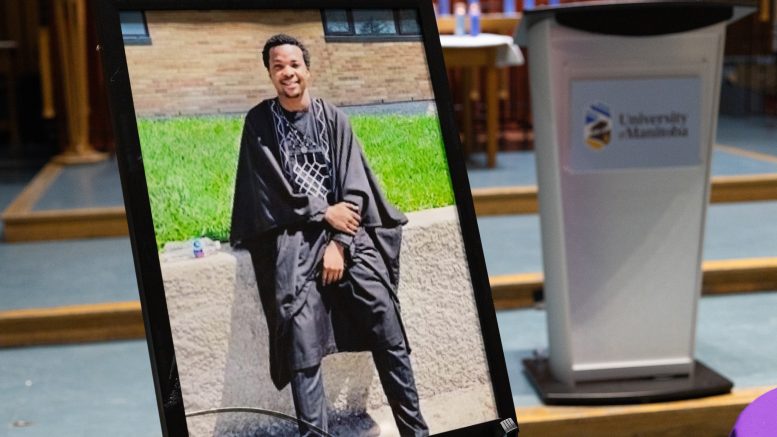

That day, she missed both those calls. Among the hundreds gathered to honour the 19-year-old’s life at a candlelight vigil at St. John’s chapel this past Friday, she struggled to contain her pain.

“He was a good person,” she said through tears. “He wanted me to be happy, he wanted everyone to be happy.”

Opaso, an economics student at the U of M, was shot New Year’s Eve at an apartment near campus by officers responding to a wellness check and died in hospital. His family’s lawyer said he was experiencing a mental health crisis. Police said he was armed with two knives.

The Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba, the police watchdog agency originally tasked with investigating the shooting, has handed its investigation over to an Alberta-based civilian oversight organization.

Surrounded by mourners, Babalola echoed a sentiment repeated by the hundreds dressed in pink and black filling the chapel pews and spilling out into the hall.

“He needs justice.”

‘Hope, resilience and the power of collective action’

Vera Keyede, Nigerian Association of Manitoba president, asked a question on the minds of so many in attendance: “When does a mental health crisis turn to a death sentence?”

Keyede was one of the speakers who went up to the podium during the ceremony. Many, from the university and from the greater community, spoke of Opaso — known to many as Zigi-Pink — the necessity of breaking down the stigma around mental health and the need for accountability, truth and justice.

Each person in attendance held a candle, and when the lights in the chapel dimmed, slowly, the first flames were lit and passed down each row, one individual lighting another’s candle, until the room swelled with warm light held in every person’s hands.

Then, the room burst into prayer, and among those singing was Damilola Ojo, Black Students’ Union co-president and newly-elected UMSU Black student rep. Like Opaso did, she has a passion for music. She realized at this point that the gathering wasn’t just about remembering Opaso. It was made up of people coming together to grieve for someone so young.

“I would never have imagined to have to do a memorial for someone who’s my age,” she said.

“That’s just what I keep going back to. Someone who’s my age and who’s in school, who is studying the exact same things as I am.”

Ojo could say little about Opaso’s death due to the ongoing investigation, but what she did say is that “we can grieve.”

“That’s something that no one can try to dictate.”

The candles kept burning long after the prayers ended. Wax dripped past the paper holders and onto the fingers of the people grieving.

Candles provide warmth and light amid dark times, explained Dola Akintan, Black Student Community vice-president student engagement.

“The flickering flame provides a symbol of hope, resilience and the power of collective action,” she said.

Akintan was another organizer of the vigil and said the need to get ready for the event in the first place was a shock.

“A few days before we all found out about what happened, we were planning to have other events to welcome new students, and suddenly we’re planning a candlelight [vigil] for one of us,” she said.

“It was a lot of emotions. Sometimes we were angry, other times we were so frustrated.”

‘Grief is a collective experience’

Leading vigils is never easy, said Edgar French, spiritual care co-ordinator for the university, but it is not uncommon for the U of M to hold these gatherings in memory of students. In French’s seven years with the university, he has assisted in more vigils than just Opaso’s, but acknowledged that Opaso’s death is exceptionally tragic.

He emphasized the importance of grieving as a collective at gatherings like a vigil, because “grief is a collective experience.”

“There’s something quite powerful that happens when we’re in this gathering together.”

That comfort is particularly valuable to many international students. Tracy Karuhogo, UMSU president and an international student herself, pointed to the comfort that she hoped Opaso’s vigil provided for other students like her.

“It was really nice to just be around community, just feeling the love of community,” she said.

Even though Opaso’s family was unable to attend the vigil in person, Karuhogo hopes the gathering gave some comfort to the family “just to know that, even though they are not here, it doesn’t mean that they are alone.”

Karuhogo has experienced the loneliness many international students face while far away from home firsthand, as well as mental health struggles of her own. Finding a support system in Winnipeg provided her with additional comfort, but in her four years in the city, it’s a task she has struggled with.

“That support system is really such an important piece, and I hope from here, people are talking […] and just know that they’re not alone,” she said.

‘If we’re not upset enough to liberate people, then what are we doing?’

Warren Clarke, a professor of anthropology at the U of M, attended Opaso’s vigil not as a professor, but “as a human being” in solidarity with the Black community and its intersectional realities that often lead to violent oppression.

Ultimately, mental health does not exist on its own, Clarke explained, and the conversation cannot begin until contributing social oppressions based on characteristics like race, ethnicity, age and class are recognized.

“Unfortunately, this is another example of the killing of Black men that’s been happening in North America and continues to stretch into our contemporary moment, which is impacting our young people,” he said.

Young Black men in colonial states face anti-Black racism and gender biases associated with their Blackness, and when the experience of being an international student is factored in, it introduces another type of social oppression, said Clarke.

“We have to keep in mind that these social oppressions impact mental health,” said Clarke.

He stressed the importance of being upset about the circumstances that lead to these vigils, and doing so in a powerful way.

“We need to be upset in a way in which we start moving the needle to liberate people,” he said.

“If we’re not upset enough to liberate people, then what are we doing?”

One of Opaso’s closest friends was fellow U of M student Hamza Liman. When Opaso first arrived in Canada about a year ago, Liman was one of his roommates.

Liman’s key message was that of justice and awareness, of encouraging people to use their voices to make sure moments like this stop repeating.

“We just need justice,” he said. “We need everyone to know that this isn’t right.”

“If no one speaks up about it, there is no change that’s going to happen.”