The experiences I’ve carried with me from a life in and out of various states of poverty were ones I frequently felt alienated by.

I was fortunate enough growing up to have created a support system and community for myself of folks who had similar experiences to mine that would combat those feelings. But university ended up reigniting that alienation.

For context, growing up I knew that I was poor. My family would move from lower working class to lower middle class when I was in my late teens, but getting there took incredible sacrifices and hardships.

Regardless, the first half of my life was full of sleeping on mattresses on the floor, blankets as curtains or doors and margarine sandwiches for lunch. I had a sense of pride about it. Back then, I felt like poverty made me strong or showed that I was built to survive things. This perspective was one I had primarily because I needed it to be true, because somehow, even if I tried to pretend I wasn’t impoverished, someone would always be able to guess my origins and make it a problem.

No matter how nicely I dressed, or even if I lied about my financial status, something would always manage to “give me away.”

The tell was often my vocabulary and my clothing. Colloquial language or slang I grew up with and second-hand clothes would act as billboards that gave others the impression that I was unintelligent.

While intelligence is relative, and there’s nothing wrong whatsoever with wearing second-hand clothes, the fact of the matter is that shame and embarrassment associated with financial insecurity are forced upon you regardless of whether or not you even believe it.

When I entered university, however, I was determined to rid myself of those feelings by going to school, not for work, but purely for the education and knowledge that felt off-limits to me.

There were several things that surprised me about campus culture, like how everyone around me seemed to have disposable income and I didn’t.

I have never been able to eat at a restaurant on campus without putting a large hole in my wallet.

Getting a cup of coffee that didn’t taste like sewage without being over three dollars was a quest on its own. I couldn’t fathom eating an actual meal at Degrees and not considering it a special occasion.

Another thing that became really apparent for me on campus is that, while people may no longer care about another person’s financial status the same way they did when I was younger, they still feel uncomfortable when confronted by poverty.

I won’t deny always talking about growing up poor, telling stories or jokes about my experiences in an attempt to lighten a mood or try to connect and relate with someone.

But reactions to this have varied depending on the crowd I’m with. Frequently, it seems that someone feels the need to provide me with “solutions.”

Apologies, unwarranted advice and well-intentioned but misplaced pity are common responses I have received over the years on campus.

I don’t want to discourage kindness, and maybe it’s my fault in the first place for sharing, but these responses, whether intentional or not, leave me with a sense of guilt and fractured identity.

On one hand, I feel like it drove me more to try and prove myself within the U of M, to claim the title of academic.

On the other hand, I felt alienated and ill-fitted within campus culture due to an inability to relate to my peers on this level. I felt a misplaced guilt for feeling like I didn’t belong in post-secondary education, like an imposter.

The irony is that I have met students over the years similar to myself who are getting degrees and going into respected fields.

These students are also disgusted at things like the prices at G.P.A’s, or how textbook costs can amount to the same price as your grocery budget.

I naturally feel kinship with those students pursuing education, even if they are no longer in the working class or in poverty, those who are “in the know,” so to speak.

It could genuinely be chalked up to the fact that if you’ve never been through it, you don’t get it — until you experience it.

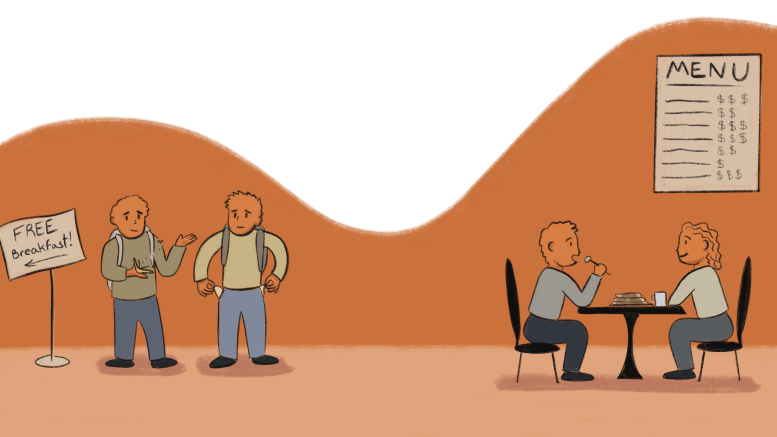

Of course, there are some initiatives on campus that I feel almost consider students who need low barrier or no cost assistance. The occasional UMSU free breakfast for example, or the decision to have free menstrual products in bathrooms on campus — which are also just beneficial for everyone.

I think it’s also important to acknowledge that, just like all intersections of identity, there are ways in which I’m privileged in life. My experiences do not represent all experiences of others who are working class or low income, but loneliness is a universal experience. Loneliness due to your socioeconomic status may not be unique, but it can feel that way when you’re not the typical demographic of student.