When Rady faculty of health sciences nursing student Jogminder Sandhu started his clinical in an acute medical surgery unit, he took the principles and approaches learned in his palliative care coursework into practice.

Palliative care is a holistic approach to care aimed at improving the quality of life for people living with a life-threatening illness and their families.

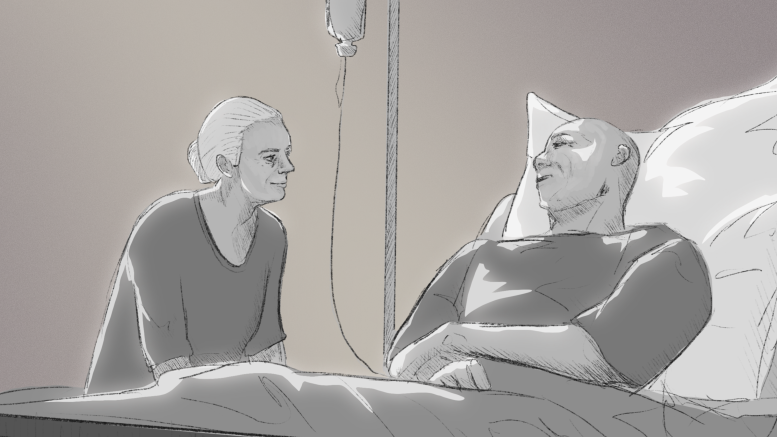

Sandhu recalls his experience with a patient who was receiving aggressive medical treatment despite the fact that their body was no longer responding positively.

Drawing from his palliative care knowledge, Sandhu suggested a palliative approach. This involved comprehensive discussions with the medical team and the patient about the patient’s goals and the need for comfort-focused care rather than curative treatments.

This illustrates a vital point about palliative care ― it is an approach that can be incorporated into various healthcare settings.

“Students will use this in any setting,” said U of M nursing instructor Jane Kraut.

“We see people with chronic illness or even close to death on any units, in any hospitals or in any communities.”

“We feel that it is a really important approach and a really important thing that we need to talk about with not just nursing students, but all health-care providers.”

Kraut previously worked as a community visiting nurse in the palliative care program of the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority.

The program, designed for individuals with life-limiting illnesses approaching end of life, focuses on holistic care and offers services within hospital units and hospice facilities.

Kraut’s role as a community visiting nurse took her directly into the lives of patients and their families.

“Our visits were a little bit longer in the community, so we could sit down and we could talk to families,” she said.

The goal was to guide families through difficult conversations about the progression of their loved ones’ illnesses, ensuring they were equipped to make informed decisions about their care.

As a palliative care worker, Kraut coordinated care and supported clients and their families on both a medical and psychosocial level.

The emotional aspect of palliative care might evoke thoughts of sadness and somberness. However, Kraut shares a different perspective.

While acknowledging the presence of challenging moments, Kraut emphasizes the honour she felt in helping patients achieve their final goals and fulfil their last wishes.

“I actually found it to be quite happy,” she said.

“I always found it to be such an honour as we got closer to the end where you’re in this moment, much like labour and delivery nurses where you’re bringing babies into the world, you’re sort of helping someone leave the world in some ways,” she continued.

Today, as a palliative and supportive care instructor at the U of M, Kraut is helping shape the next generation of compassionate and skilled health-care professionals and equipping them with the skills to engage in difficult conversations about death and grief.

She emphasized that effective communication lies at the heart of navigating these conversations. To Kraut, getting to know someone on a personal level and understanding their hopes and fears is the key.

“I think students, once they know that’s the best way to kind of bridge these conversations, it’s so much easier to do that,” she said.

Kraut and her team integrate practical scenarios into their teaching, encouraging students to initiate conversations with partners, family and friends to normalize discussions about end-of-life wishes.

Kraut also addressed the societal taboo surrounding conversations about death.

She emphasized the importance of incorporating death education into the curriculum, allowing individuals to approach the subject openly and candidly.

“The earlier we talk about death and dying, it becomes less taboo,” she said.

By familiarizing society with these discussions early on, the fear and uncertainty often associated with death can be mitigated.

Kraut encourages aspiring nurses and students starting off in palliative care to embrace curiosity and compassion, rather than fearing they might say the wrong thing.

In her experience, building a personal rapport and understanding patients’ goals of care were fundamental to providing quality palliative care.

“Taking two or three minutes out of the day to just sit and learn something about your client and their family can really make a difference in terms of understanding what they want out of their care,” she said.

“When we start in our education career as nurses, we’re really focused on the patient, getting their vitals, giving their medication,” Sandhu said.

“But palliative has shown me how an individual’s health is beyond just them, and I will take that into account especially going into surgery next semester.”