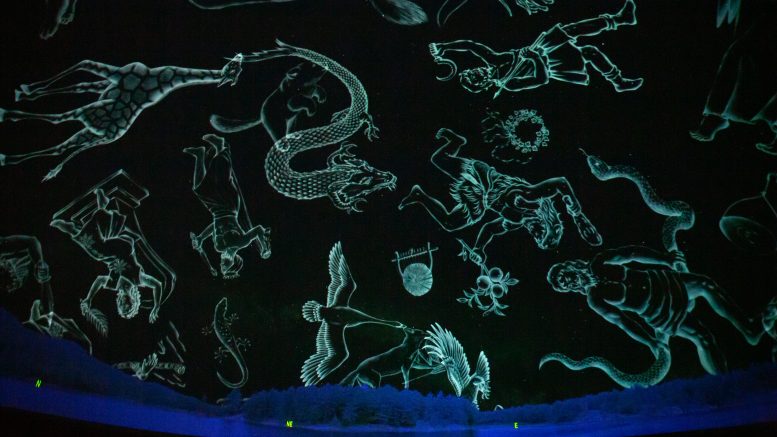

On the third floor of University College, in room 394, is the Lockhart Planetarium.

This facility at the U of M Fort Garry campus serves as an immersive teaching and public outreach space for the department of physics and astronomy.

U of M astronomy instructor and director of the Lockhart Planetarium Danielle Pahud described it as “the university’s best kept secret.”

In this 48-seat, eight-metre diameter dome, the sky is quite literally the limit.

Construction of the Lockhart Planetarium began in the early 1960s. However, it underwent significant renovations from May 2017 to early 2020.

The facility previously used an opto-mechanical projector, which Pahud described as “a big sphere with a bulb inside, with holes and lenses poked into it.” This projector is now encased in glass within the tunnels next to the Duff Roblin building.

The modernized space features a Spitz SciDome 2400 projector system and digital software that pulls data from professional astronomy databases, such as those at NASA, to showcase a hyperrealistic view of the stars, planets in our solar system and exoplanets.

“The number and the location and the size of all of the planets that are being shown are simulations, but the simulations are accurate to what we know about those worlds,” Pahud said.

The Lockhart Planetarium hosts open houses on the last Wednesday of every month, welcoming members of the U of M community and general public. The next open house will be held on March 29 at 7 p.m.

Pahud said that the experience of the planetarium often evokes awe among visitors.

“When you look up outside, you’re subject to cloud cover or needing a big telescope,” she said. “In the planetarium you don’t need any of that and you can still get that same reaction, which is kind of fun.”

To Pahud, inspiring curiosity in people about astronomy is the fundamental goal of the Lockhart Planetarium.

“I hope to inspire people to look up when they’re outside a little more,” she said. “Thinking about our place in the universe both physically and philosophically is important, and I think astronomy is a really good way to unlock that.”

“I also feel like sharing knowledge and sharing what we know about astronomy is a privilege,” she added.

Like Pahud, many researchers at the U of M department of physics and astronomy share a similar ideology in encouraging curiosity about space and beyond.

Samar Safi-Harb, a professor in the department of physics and astronomy, and Canada research chair in extreme astrophysics, uses her research as a means of sparking curiosity about science.

“There’s a lot of discovery in astrophysics,” she said. “When you look at the sky, you always find something new and interesting that you never even expected, so it’s a great place for discoveries, which is great for attracting students as well into the field.”

After completing her post-doctoral fellowship at NASA, Safi-Harb came to Winnipeg to jumpstart the U of M astronomy program, which was absent at the time.

Her research examines extreme phenomena associated with the death of stars.

Stars, like the sun, eventually run out of nuclear fuel. Very large stars explode in a high-energy, dramatic explosion called a supernova. These explosions lead to the formation of heavy elements, neutron stars and black holes.

To observe these explosions, Safi-Harb uses satellites and telescopes across the electromagnetic spectrum. By studying these explosions and their byproducts, she is able to explore the physics of the extreme.

“It’s like this nearby lab in space, which allows me to understand the physics that people here on earth cannot,” she said.

Also engaged with the study of astronomy is U of M associate professor in the department of physics and astronomy Jayanne English.

English looks at the motions of galaxies — stars and their planets, dust, gas and dark matter bound together by gravity — by using their gas.

In a project with Jason Fiege, an associate professor in the department of physics and astronomy, the researchers use computational astrophysics to look at how a galaxy is rotating.

English explained that there are odd anomalies associated with this motion, which move in a different direction.

“They can be caused by two galaxies interacting together, having a gravitational pull toward each other,” she said.

“We can look at outflows of gas from galaxies, and this tells us how galaxies evolve with time, how they change, how they mature, what kind of new galaxies they’re going to turn into.”

Additionally, English is an expert in astronomy image-making and visualization. Using digital photographic data, the researcher is able to make colour maps for astronomers and images for public outreach.

“It’s a balance of both the science that is evident in the data and the art which will help engage the person, so that they spend time looking at the image and learn about this science,” she said.

English’s curiosity in astronomy began as a child. Her research in the field is an interaction between herself and the world around her.

“I think of it as becoming engaged with nature, intimate with nature,” she said.