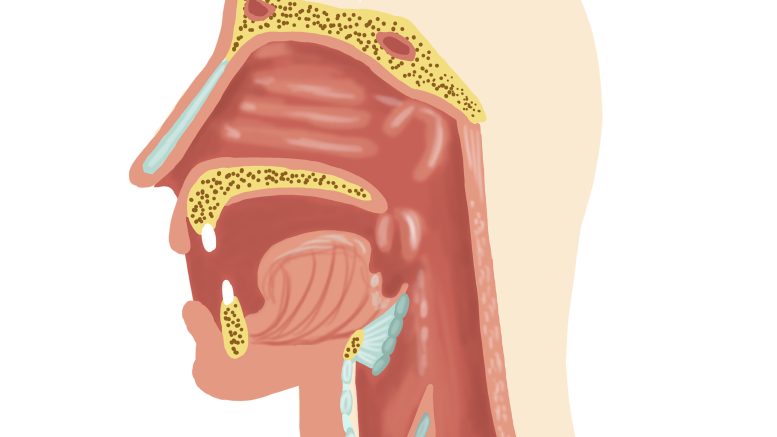

There are many organs that help produce speech, such as the tongue, lips, teeth and other structures within the mouth like the palate.

Phonetics — a branch of linguistics — studies the way speech sounds are produced and perceived in human language.

Robert Hagiwara, an assistant professor in the U of M department of linguistics, has done extensive research in phonetics, particularly on the properties of the American “r.”

The way the “r” is pronounced in North American English is unusual compared to most “r”-like sounds, which are usually trills in other languages.

A trill is a series of flaps — a quick flip of the tongue against the palate — that produces sound. The Spanish “r” is an example of a trilled consonant.

In 1995, Hagiwara wrote a paper about the acoustic differences between the way men and women pronounce the American “r.” He said that at the time, women’s voices were not as well-studied.

A review of phonetic literature on vowels from 1992 found that only four per cent of studies had female data.

Part of the reason for the lack of research on women’s voices was the idea that they were an othered version of men’s voices. There was a widespread yet incorrect assumption that the impact of anatomical differences could be calculated and accounted for without actually observing women’s voices.

One major anatomical difference is that female vocal tracts are about 20 per cent shorter than male vocal tracts. The internal proportions of their vocal tracts are also different.

For males, the oral cavity as measured from the incisors to the back of the throat is shorter than the upper throat. For females, the oral cavity, measured the same way, and the upper throat are the same length.

An effect of these differences is that women’s vowel formant frequencies are higher. Formants are the natural frequency in which the vocal tract vibrates.

Hagiwara explained that what sets the American type “r” apart is its unusually low frequency.

Hagiwara intended to study the interaction between the expectation of a low formant frequency for the American “r” specifically and the expectation of higher acoustic cues from women generally.

However, after an initial investigation that compared the American type “r” to a similar sounding “r” in another language, he found that the relationship between men’s and women’s American “r” was so complex that it had to be analyzed alone.

With a new repertoire of data from a previously understudied population, Hagiwara had the tools to investigate several unexplored issues in acoustic phonetics.

He was able to demonstrate that Canadian English and Southern Californian English were similar, but not in the ways that had been previously assumed.

Hagiwara explained that his work is centred on determining the validity of assumptions such as this.

“I do this work that involves filling in gaps in what we actually know versus what we believe and turn out not to have clear evidence for,” he said.