Monkeypox, first identified in non-human primates in 1958, has become a global outbreak with over 50,000 cases worldwide. On Aug. 19, Manitoba Deputy Chief Provincial Public Health Officer Dr. Jazz Atwal confirmed Manitoba’s first case of monkeypox.

University of Manitoba assistant professor and Canada research chair in emerging viruses Jason Kindrachuk shed some light on the emerging viral disease and the risk factors associated with it.

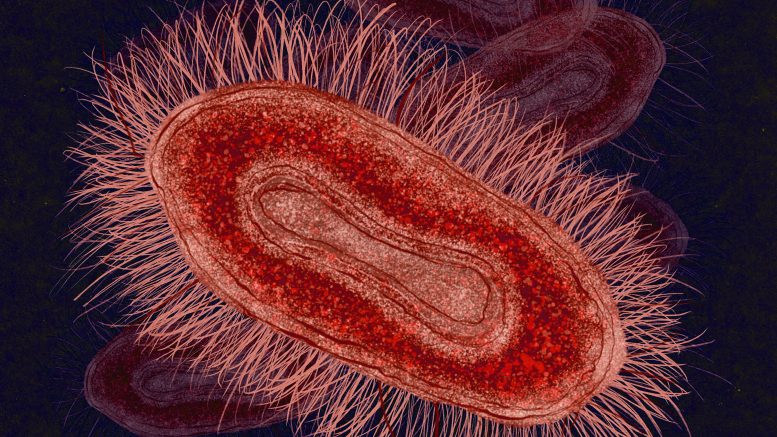

Monkeypox, an orthopox virus belonging to the same family of virus as variola — the causative agent of the smallpox, cowpox and vaccinia viruses — is largely transmitted through close extended contact.

“Things like contact with lesions through direct physical contact are largely implicated in transmission,” Kindrachuk explained.

“There may be some respiratory component to monkeypox, though that’s not as well characterized. There have been some events that look like they relate back to droplets or aerosols in short distances,” he added.

The issue remains concerning whether or not the monkeypox virus has evolved or whether we have been able to recognize new cases. Human cases in endemic regions from as early as 1970 were transmitted from animals to humans, primarily by contact with rodents.

“Since the reported cases from the Nigerian outbreak, and then obviously what we’re seeing now, we have seen more sustained human-to-human transmission,” Kindrachuck explained.

Kindrachuk noted that the majority of newer cases appear to be associated with sexual contact and are over-represented by men who have sex with men, something that has not previously been reported for monkeypox.

“We have to be somewhat cautious in saying that this is a brand new phenomenon,” he said.

Kindrachuk went on to explain that earlier surveillance from 1970 onwards was largely limited and stigma was attached to self-reporting.

Symptoms of the viral infection include a rash and general symptoms such as a fever, chills, headache, muscle pain, joint pain, back pain and swollen lymph nodes. These symptoms are often developed five to 21 days after exposure to monkeypox and may last up to four weeks.

Genital lesions have been commonly observed with the current outbreak as opposed to previous cases, where lesions were mainly present on the face, hands, legs and body.

Additionally, an asynchronous development of lesions has been seen with the current outbreak.

“Lesions in, say, the groin may be in a different developmental stage than those that are presenting on the face or on the hands,” Kindrachuk said.

This is clinically different from historical cases where lesion development was at the same stage.

Historically, the two subtypes of monkeypox virus — known as “clades” — have had higher death rates than what is currently being seen. The Congo basin clade had a fatality rate of about 10 per cent, while the West African clade had a fatality rate of 3.6 per cent. A significantly lower case fatality rate is seen in the current outbreak.

“We don’t necessarily know if it’s behaving differently than clade 2a, the former West African clade, but the case fatality rate continues to appear to be quite low,” Kindrachuk said.

Also, children have been identified as being at low risk for contracting the disease.

With Manitoba’s first case identified, Public health officials have confirmed an ongoing investigation.

“The unfortunate reality is, we all assumed that this was going to happen. I think the bigger focus always has to be, ‘how do we reduce the impact when those cases show up?’” Kindrachuk continued.

“In particular within the communities being affected, how do we get vaccines, messaging and recommendations out to those communities in a respectful and transparent manner.”

Canadian universities and health authorities are becoming more proactive in minimizing the risks of infection on campuses. Prior to the University of Manitoba fully opening its doors and welcoming students back on campus after over two years of remote learning, Manitoba Public Health set up a pop-up clinic offering the monkeypox vaccine to eligible individuals at the Fort Garry campus.

Manitoba has also expanded the eligibility for immunization to those who have been in close physical contact with an infected individual, or as a preventative measure for those who are at high risk of exposure.

As our understanding of monkeypox progresses and researchers continue to find new insights into the mechanisms of the viral infection, Kindrachuk explained the importance of providing the community with messaging and resources that help us seek out information and help when needed.

“The group that I’ve been working with at WHO (World Health Organization), the guideline development group, we’ve provided a pretty broad clinical management infection prevention control document based on all the information we understand about monkeypox,” he said. “We’re currently updating that.”

Kindrachuk advised that we remain cognizant of the symptoms associated with monkeypox, get information from reliable public health resources and if there are any symptoms of general unwellness, see a health-care practitioner.