Last month the Manitoba government announced that by October 2023 it plans to raise the provincial minimum wage to $15 per hour. The announcement was made in part to address concerns regarding the significant inflation that Manitobans may continue to struggle with in the coming months.

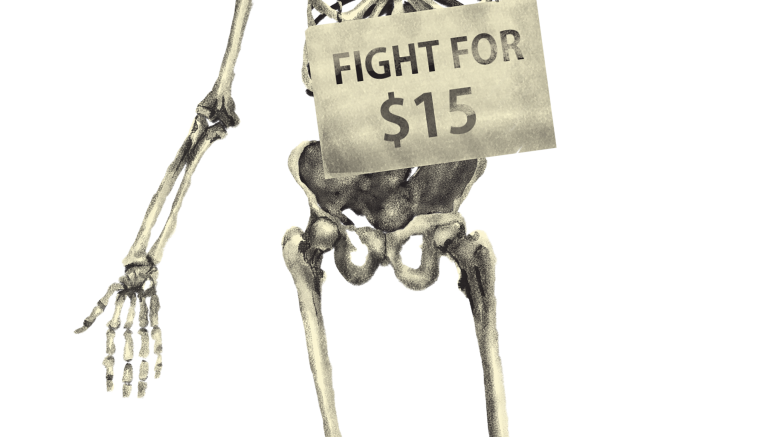

Well, minimum-wage workers should be thrilled! After all, they’ve finally won that “Fight for $15” that they’re always going on about. Finally a win for underpaid workers, right?

Not exactly.

Don’t get me wrong, a $15 minimum wage is obviously an improvement over the current $11.95 hourly rate. That being said, just because it’s an improvement doesn’t mean it’s sufficient.

There’s a big difference between a minimum wage and a living wage. A living wage is an hourly rate that takes into account how much workers would really need to earn in order to pay their bills and take part in their communities. In other words, it’s the amount needed to live, rather than simply survive.

The Manitoba office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), an independent, non-partisan research group, calculated that the living wage for a Winnipeg family of four with two earners in 2022 should amount to $18.34 per hour. For single parents with one child, this wage was found to be $25.28.

But aren’t these minimum wage-paying jobs just “starter jobs?” Aren’t they just positions worked by young people who need a bit of money before they study up, graduate from university and get a “real” position somewhere? Why consider wages needed by families and parents, when these jobs are only worked by teens and seniors with too much time on their hands?

These assumptions are of course, incorrect. Minimum wage workers often support families, and as of 2019 nearly half of all Manitobans making minimum wage were over the age of 25. Approximately one-third had already graduated from a post-secondary institution.

Well, what about the “Fight for $15?” Why would workers push for a number that isn’t enough?

Way back in 2015 when the “Fight for $15” movement emerged in Canada, maybe $15 was enough. But as the province is aware, there is inflation to consider.

The Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator can be used to determine that $15 in 2015 had the same purchasing power as about $18 in today’s money. Given this three-dollar difference in real value, I guess the provincial announcement could be considered a victory if the movement changed its name to “Fight for $12.”

Considering that Manitobans won’t actually see their pay increase to $15 for another year, and that the Manitoba minimum wage was already $11 per hour by October of 2015, the actual ground gained seems minimal at best.

But the dollar amount itself isn’t the only reason the announcement doesn’t feel like a meaningful victory. Working for minimum wage comes with a feeling of being disposable and devalued, a feeling put into words by actor and comedian Chris Rock during a sketch on SNL in the ’90s:

“Do you know what it means when somebody pays you minimum wage? You know what your boss was trying to say? It’s like, ‘hey, if I could pay you less I would, but it’s against the law.’”

This sense of being given as little consideration as is legally possible pervades many aspects of minimum and low wage roles. For instance, due to government regulations that allow employers to change their employee’s schedules at any time, minimum wage workers often deal with unstable and inconsistent scheduling, which can mean unstable and inconsistent income.

Low income earners can also have a difficult time receiving any benefits outside of wages. Currently, the Manitoba government does not require paid sick leave to be offered by employers, and minimum wage workers are those least likely to receive any paid sick leave from the companies they work for.

Additionally, Manitoba’s health plan does not cover services like routine vision care for those ages 19 to 65, or non-emergency dental care. In a 2020 CCPA Manitoba research report, only one out of 42 minimum wage workers interviewed had any benefits at their job, with many having difficulties affording health-related services like dental care.

This devaluing of low wage earners was highlighted by the shift in discourse surrounding them during the pandemic. Suddenly, the government classified many minimum wage workers as “essential,” working in “critical services.”

How can the province call these workers essential while leaving them at the mercy of their employers for vision and dental care? Does the government consider eyes or teeth to be non-essentials? Should “critical” workers be forced to choose between losing out on a paycheque and going into work sick?

While the minimum wage increase is better than nothing, it comes too late and does too little to drastically change the quality of life for minimum wage earners.

If it is truly concerned with improving the lives of minimum wage employees, the province should work to institute a living wage for all workers. Further, it should amend the legislation around employee scheduling to require notice of a schedule change, and require mandatory paid sick leave and dental and vision coverage to be provided to all employees.