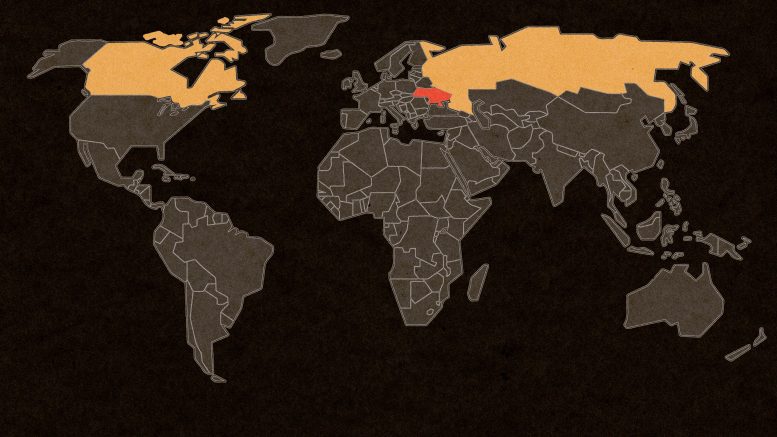

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine this week, Canadian editorial boards have almost universally labelled Vladimir Putin as a deranged leader bent on wanton destruction and ignored Canada and NATO’s role in provoking this aggression. Although Putin’s actions should be condemned internationally and Canada should extend support to Ukraine, the current way that support is manifesting in military expenditure should be of serious concern — especially considering some of the political context this war has unfolded under. It is crucial, as this crisis plays out, that we condemn Russian aggression while also recognizing that Canada has historically played a damaging and destabilizing role in the region. Canadians must resist falling into uncritical wartime rhetoric about Canada’s myth-worthy peacemaking identity. Canada has exploited Ukraine as a proxy site for its own ambitions and, as such, Ukraine has found itself sandwiched between the aspirations of two major powers in the world.

Canada has been a crucial cog in providing equipment and training to Ukrainian military forces and fringe political groups since the 2014 Canadian-backed coup of former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych who was torn between an association agreement with the European Union (EU) or a Russian relationship, only swaying to the latter toward the end of his presidency.

Yanukovych’s leadership was not without warranted controversy, though. Most of his votes came from the eastern regions of Ukraine which have strong ethnic and linguistic ties to Russia, and Putin’s political support for his candidacy made some people skeptical of the election results. As such, following his first election in 2004, parts of western Ukraine erupted in protest. In December 2004, the Supreme Court called for a re-election and Yanukovych lost. The election nearly prompted civil war between east and west Ukraine. Yanukovych would later win the 2010 election.

Fast forward to the late months of 2013 and Yanukovych made the controversial decision to back out of talks with the EU about reaching an association agreement. The decision was ill-received in the western parts of Ukraine and demonstrations, which lasted months into 2014, broke out in Kyiv. The demonstrations ultimately culminated in regime change. One year later, the Canadian Press released statements from officials in allied European nations that implicated Canada as a crucial actor in Yanukovych’s downfall.

The nationalist government replacing Yanukovych immediately removed Russian as one of Ukraine’s official languages, angering Ukrainians in the eastern regions. Referendums were held in Ukraine’s Donbas region and Crimea, which led to the informal independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. The referendum and subsequent separation from Ukraine were formally the main sources of civil war in Donbas. Further, Crimea held a referendum that showed 95 per cent of voters — for context, 50 per cent of the votes were counted — were in favour of seceding from Ukraine to join Russia.

These referendums were the source of significant international dispute. Many western nations saw them as illegal and Russia, for obvious reasons, embraced them, later motivating Putin to annex Crimea and funnel resources to the Donbas region to support the pro-Russian front. Putin has since used this story as justification for his condemnable invasion of Ukraine. Regardless of where one might stand in terms of the legitimacy of the referendums, it is not difficult to see how the 2014 coup played a key role in destabilizing Ukrainian-Russian relations, helping set the stage for the mass violence we are now witnessing.

As John Foster — the author of Oil and World Politics: The real story of today’s conflict zones — notes, “Part of the agreement underpinning the USSR’s dissolution was western assurance that it would not expand into Russia’s sphere of influence, a pledge NATO most recently violated […] The west accuses Russia of interference in Ukraine. Russia points to a 2014 western-inspired coup in Ukraine and legitimate grievances of Russian-speakers in the breakaway Donbas republics.”

Since 2015, Canada has spent significant resources arming and training Ukrainian fringe groups to help fight the proxy war in the Donbas region and prepare Ukraine for a potential invasion — a move that has provoked further tensions. Canada has consciously trained and armed neo-Nazi groups in Ukraine as a means to this end. According to investigative reporting done by the Ottawa Citizen, “The Canadian military was warned in 2015 before starting its Ukraine training mission about the dangers of the far-right within the Ukrainian military ranks, but the senior leadership largely ignored those concerns.” Subsequently, Canadian soldiers were photographed with the Azov Battalion — an openly neo-Nazi paramilitary group that sports swastikas and SS symbols on their military equipment.

While it would be reductive and blatantly false to say that a majority of weapons and training are falling into the hands of neo-Nazis, it should, nonetheless, be a concern of Canada’s considering it is extending $7.8 million in lethal weapons and a $500-million loan to help with the war effort.

While arming Ukrainian civilians — some of whom will be members of far-right factions — is an inevitable consequence of war, Canada shouldn’t be involved in it. History shows funding proxy endeavours will do far more damage in the long run. Take Afghanistan and the Mujahideen as an example: radical groups disproportionately benefited from western military aid in the 1980s and the state hasn’t stabilized since. By sending military resources to Ukraine, Canada could be contributing to turmoil that could last far longer than the Russian invasion.

What makes military support especially concerning is that Canada stands to economically benefit from this war, Ukraine’s instability and from Russia’s alienation on the international stage.

Just like many wars before it, pundits have taken a zero-sum game approach to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and neglected internally judging their own country’s role in provoking violence via proxy. On Jan. 26, Canadian Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland noted “Canada is supporting Ukraine […] because we have a clear and urgent national interest in the situation there.” This vague statement, under a critical light, exposes that Canadian interest in the war is less about the principle of international order than it is about what Canada poses to gain from the instability it produces.

One of the more obvious interests Canada may have in alienating Russia from its relationship with Ukraine and its international reputation is Russia’s major role in natural gas and oil exports — it is the largest exporter of natural gas and second-largest exporter of oil. A day after Freeland noted Canada’s stance on Ukraine’s crisis, U.S. Under Secretary for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland mentioned that Russia’s Nord Stream 2 — an oil pipeline being constructed to Germany — would be barred from completion. “If Russia invades Ukraine one way or another […] we will work with Germany to ensure [Nord Stream 2] does not move forward.”

Freeland has also been very vocal about her “significant concerns” regarding the pipeline and the Russian invasion of Ukraine may have played directly into Canada’s ambitions. Shortly after Russia invaded, the U.S., Canada and other allies placed sanctions on the company building Nord Stream 2. Meanwhile, Canada continues to suppress domestic movements against its own oil sector and incursion of Indigenous hereditary land.

Despite Canada extending support for Ukraine, true resolve toward a peaceful end remains to be seen. The best option going forward would be to listen to Russia’s diplomatic concerns and reach an agreement in exchange for Russia’s military withdrawal from the sovereign state. However, this appears to be a pipe dream. Instead, Canada continues to sow discord and promote further war. Instability appears to be Canada’s ideal outcome and, like Russia, Canada has chosen to violate Ukraine as a proxy space for its geopolitical interests.