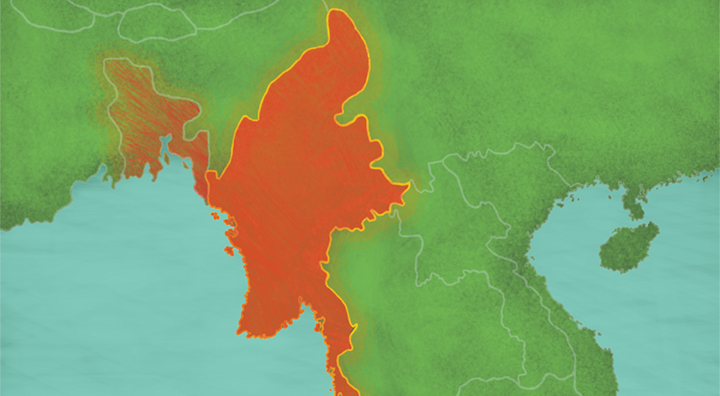

The state-sponsored oppression in Myanmar of the Rohingya, a minority ethnic group composed primarily of Muslims often described as “the world’s most persecuted people,” has swiftly become one the gravest humanitarian crises of the 21st century.

The crisis has resulted in more than 700,000 displaced Rohingyas – a majority of whom have fled to Bangladesh, only to weather appalling living conditions in refugee camps and around Cox Bazar without proper shelter, sanitation, and clean drinking water.

The refugee camps in Bangladesh are now the world’s largest “mega-settlement” of displaced people.

The world’s lack of interest in protecting and advocating for Rohingya is troubling: relief in the form of aid and attempts to reach a peaceful solution through diplomatic channels is not enough. The lack of attention to the plight of Rohingya internationally has emboldened the Myanmar to continue the persecution of the Rohingya, resulting in severe human rights violations.

It is imperative that the Western countries understand the history of the country in order to fully grasp the severity of the atrocities and violence faced by its ethnic minority.

A 2015 legal report titled “Persecution of the Rohingya Muslims: Is Genocide Occurring in Myanmar’s Rakhine State?” published by Yale law school succinctly captures the extent of Myanmar’s crimes, historically and currently.

Since gaining its independence in 1948 from Great Britain, many regimes unsuccessfully attempted to rule the newly independent state of Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, until a military general took control of the country in a 1962 coup.

Since 1978, the military has targeted Rakhine State – home to 1.1 million Rohingya – and has used abuse, rape, religious persecution, marriage restriction, population control, and murder as methods of systemic ethnic cleansing. This action has resulted in mass migration of Rohingya into neighbouring countries in the Indian subcontinent for decades.

Nation-wide economic stagnation prompted the population to partake in widespread protests – which ultimately turned into pro-democracy protests in nature – during which the military regime killed thousands of civilians and instituted its control on the state.

However, the military government continued imposing oppressive laws against the Rohingya, including the denial of citizenship as a result of a 1982 citizenship law. Legislation reduced the legal status of the ethnic minority to foreigners or unlawful residents. The absence of citizenship meant limited access to education, health care, and no voting rights.

The state then came under the temporary control of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) which held Myanmar’s first democratic elections. The National League for Democracy under the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi then emerged victorious in the 1990 elections.

In turn, the military imprisoned many pro-democracy activists, NLD leaders including Suu Kyi, and retained control of the state, making Suu Kyi the torchbearer of democracy and peace for which she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991.

Myanmar’s long struggle to form a democratic government gives the West an illusion that a country with a decades-long journey towards democracy cannot possibly oppress a minority group based on their religious beliefs and without this historical context it is impossible to “enlighten” the West on a crisis that is more commonly shrugged off as a recent and stand-alone crisis of our times as opposed to an ongoing one.

The killing of nine Myanmar police officers in October 2016 ratcheted up the nation’s ethnic tensions. The persistent use of state power to persecute the Rohingya prompted violent action by the militant Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, which further escalated tensions.

Since the beginning of the crisis, Canada has limited its response to expressing mere concern, working through diplomatic channels, and providing monetary assistance – which is certainly not enough when one considers the gravity of the crisis.

Canada, along with international organizations such as the United Nations, must investigate the role of state counsellor of Myanmar, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and honorary Canadian citizen Suu Kyi in this matter, along with immediately imposing economic sanctions on the Suu Kyi government which has attempted to justify the murdered Rohingya by labelling them terrorists.

Last week, Adama Dieng, the United Nations special adviser on the prevention of genocide, said that firsthand accounts of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh “point to the intent of the perpetrators to cleanse northern Rakhine State of their existence,” which would be considered genocide if proven in the International Criminal Court (ICC).

An ICC referral – which can only happen through United National Security Council – is a channel worth exploring to hold the government of Myanmar responsible on an international platform for committing heinous crimes against the Rohingya.

Political grandstanding is not enough.

The European Union has collectively condemned the actions of Myanmar’s government that amount to ethnic cleaning – without any real advocacy for the Rohingya or efforts to resettle them in Europe.

In October of last year, Canada appointed Bob Rae as a special envoy on Myanmar to investigate the gravity of the military crackdown. Rae’s request to fully access the Rakhine State of Myanmar was denied and the Trudeau government awaits Rae’s final report to respond appropriately.

Yet we can not wait on bureaucrats while crimes against humanity are being carried on a massive scale. Canada must lead by example and undertake a proactive role in the resettlement of Rohingya refugees in Canada and in the West. Bangladesh cannot single-handedly shoulder the responsibility of 700,000 Rohingya refugees.

One can certainly hope that the Trudeau government will promise to bring a considerable number of Rohingya refugees into Canada closer to the 2019 election in an attempt to score a few political points, but failure to act quickly and stand up for the Rohingya will result in a lost generation of Rohingyas.

All in all, the entire international community is to blame for its failure to respond swiftly to this plight.