University of Manitoba’s department of Native Studies hosted university lecturer Gina Starblanket on Nov. 29 as part of their weekly colloquium series, “Revisions and revitalizations: Native studies in the future.”

Starblanket, a member of the Star Blanket Cree Nation in the Saskatchewan portion of Treaty 4 territory, presented her work that examines the intersection of treaty implementations and Indigenous-state relations, and looking beyond state-based mechanisms of treaty rights and recognition.

“My dissertation research broadly takes up this move that I have noticed and that I think is a really significant shift in Indigenous political mobilization over the years where Indigenous people are increasingly drawing on our own nationhood,” Starblanket said.

“This shift that I’m taking up and describing involves the ways in which many people are looking beyond state-based mechanisms of rights and recognition,” she added.

“So this paper, or this work, explores how this shift in context – and specifically the move away from colonial methods of engagement and colonial ways of understanding treaties as land sessions, as transactions – impacts Indigenous peoples’ positions within complex networks of interrelationship, such as our treaty relations.”

Treaties

Starblanket noted that the nature of the relationships that bind Indigenous people to treaties has gained distinctiveness by becoming an inherited relationship. Still, she highlights that there remains a responsibility for Indigenous people to shape treaties.

“When Indigenous people took treaties it was a way of bringing newcomers into our pre-existing relationships with the creation and teaching them how to live on this land,” she said. “That was a responsibility we had as students of this land.”

“So we cannot simply break them […] when they no longer suit us.”

Indigenous-Crown treaties long pre-date Confederation. Starblanket said the historical relativity of treaty-making, one of Canada’s “oldest political institutions,” is one that should not be ignored because of the ways it has been repressively narrated by the state.

“Doesn’t that give the state a lot more control in defining how it is we understand our own institutions?” she asked.

“Rather, what we need to do is to think consciously and critically about the implications of such dissociation,” she continued. “We have a task as treaty partners to figure out how we are going to inhabit them in a way that maintains our integrity and our vision of what they should represent.”

Indigenous treaty interpretations

Starblanket said she grew up in a community where treaties represented “the birth of a living, breathing, and growing relationship that is greater than the sum of its parts.”

This narrative, which Starblanket regards as the prototype of the original treaty negotiations, provides a dynamic framework that produces mechanisms of peaceful coexistence in a non-hierarchical fashion. This framework, she suggested, enables the preservation of both the culture and legal authority of Indigenous communities.

The Chief Paskwa Pictograph

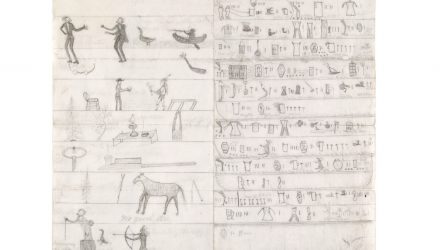

In her dissertation, Starblanket examined archival records of Indigenous written and oral histories that give meaning to the context surrounding treaty negotiations. One such record she examined is a pictograph made by Chief Paskwa after Treaty 4 was signed in 1874.

The pictograph is split into two different parts. The first panel on the left is interpreted as representing the nature of treaty relationships. The panel on the right reveals the extent through which this relationship manifested itself in the years leading up to 1877.

Starblanket proposed that analyzing the document can reveal significant elements of the nature of treaty negotiations and their interpretation, as understood by their Indigenous signatories.

A pictograph drawn by Chief Paskwa representing the nature of treaty relations following the signing of Treaty 4 in 1874.

“The [left] panel,” she said, “also includes an image of a horse tied to a stick with the words ‘No Good’ written under it. This may refer to the notion that treaties were not meant to restrict Indigenous peoples’ movements or traditional ways of life.”

Another item in the pictograph is the stretched-out arms of the two side-by-side figures illustrated in the first row of the right panel and the downward facing arm in the subsequent years. Starblanket said the outstretched arms have been interpreted to reveal the impression Indigenous signatories had of negotiations being the treaties themselves, hence the living dynamic they attributed to treaties.

Starblanket said in the years that followed it became clear that Crown representatives had no interest in meeting on a yearly basis to continue negotiations and renew the relationship, hence the illustration of the downward facing arm.

Treaties as land surrenders

On the other hand, Starblanket said the narrative of treaties being the surrender of land and legal jurisdiction in exchange for a fixed set of rights has been long maintained by Canadian society.

“This assumption is reflected in the description of treaties, offered by Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, which suggests that at their base, treaties were land surrenders on a huge scale,” Starblanket said.

“It’s not just the government that holds this position,” she added. “Some of the introductory textbooks, and even the textbook that I’m using for Native Studies 1220, they describe treaties as the great land surrender treaties.”

Starblanket suggested that this narrative “of containment” is one that is static and frozen in time, foreclosing the possibility of change.

“This [narrative] puts Indigenous people in the position of being dependant on Canada for the recognition and protection of our rights,” she said. “It reproduces that colonial dynamic. It denies Indigenous peoples’ sovereignty and political rights as independent nations under international law.”

Reviving relationality

“To me this fundamental distinction in understanding treaties, either as relationship frameworks or as fixed term transactions, lies at the root of many of the primary issues in the Indigenous-state relationships today,” Starblanket said.

She said that despite the federal government’s continual reference to a nation-to-nation relationship, “there remains a disconnect between the theoretical acknowledgement of treaties as relations and the way in which they are enacted in Canadian law and policy.”

“[Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada] never allowed for the notion that [treaties] did not represent sales and surrenders of land,” she said. “It doesn’t integrate the Indigenous perspective on the fundamental nature of the underlying relationships,” she added.

“That’s one of the biggest limitations of rights-based frameworks or of the ways in which treaties have been taken up in terms of the court’s interpretation of treaty rights that are recognized by the Constitution Act in 1982.”

Starblanket referred to some of her work with First Nations communities in Saskatchewan to highlight that the resurgence of relationality – understanding and being aware of one’s own perspectives as embedded within social structures – starts with Indigenous communities realizing the treaty interpretations of their ancestors.

“As Indigenous people, living our traditional laws is not dependent on the recognition by the Crown but involves looking to our values and principles to inform our contemporary actions and interactions,” she said. “So treaties can be evoked in really significant ways to inform how a person or a community enacts its own jurisdiction and legal principles in its engagement with external parties.”