The rich keep getting richer, and the poor keep getting poorer. It’s a common sentiment.

It’s a sentiment with weight, too – right here in Manitoba, Winnipeg’s poorest neighbourhoods have fallen further below average within the last 30 years, while the richer neighbourhoods have seen a relative rise in those same three decades. While these last 30 years have widened the economic gap between the rich and the poor, the next 30 may herald an even more sinister future.

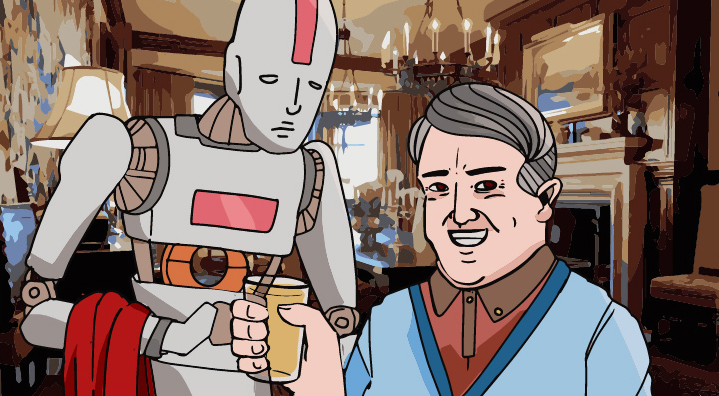

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been lauded as the future of a great number of things: video games, sexual partners, and perhaps most prevalent even today, workplace automation. As the years go by, automated technology has shoehorned itself into our daily lives. Self-checkout aisles in stores allow you to scan, bag, and pay for your own products, all without the common awkwardness of human interaction. You can insert coins into a chair to massage you at the mall. On the slightly more fantastical side, the ominously-named Cafe X utilizes “robot baristas” to produce a latte in seconds, and Korean tech company LG released the Airbot just this year, a shiny, smooth-edged robot designed to help guide people around airports.

You might ask yourself: what’s wrong with the extra income garnered by robots with less human labour? Consider what all the aforementioned uses of AI have in common. They are inherently profit-driven – and the profit seeks to solely benefit the wealthy and push out the economically disadvantaged.

The $15.7 trillion that AI is expected to add to the global economy by as early as 2030 comes almost fully by expenses paid and gained by members of the upper middle classes. The majority of that money will be made through improving the life of the wealthy: automated cars, higher-quality technology, and all-around expensive products that serve to make their lives even easier than they are now. 42 per cent of that money is expected to come from automation in the workforce.

Job automation through technological advancement – or the displacement of jobs available to humans – is generally focused on low-income careers often pursued by people without a post-secondary education. Jobs considered at high risk of being automated include taxi drivers, cashiers, and fast food cooks. Or, typically, jobs for young people, for busy people, for poor people.

The typical argument that increased use of AI in the workforce will make jobs as it takes them away is rife with half-truths. Some jobs will be made, but one must wonder what the nature of these jobs will be. As AI works to take away entry-level jobs without the prerequisite of secondary education, jobs that will be made through the upkeep of this AI will generally not be as accessible.

Current statistics speak similarly, with a recent study from the National Bureau of Economic Research finding that for every new robot added to the workforce, between 3 and 5.6 jobs held by humans were lost.

Even AI created with the intention of promoting societal good – at the same convention that revealed the LG Airbot, a robot designed for children with developmental disabilities named Leka was also presented – there exists an obvious divide in who can and cannot partake: Leka will cost between US $700 and $800.

Think a little bigger. AI has already been taught to discriminate amongst humans. There is the AI chatbot that learned to be racist from human users in less than 24 hours, and software that is currently being used to identify criminals more likely to re-offend, based on an algorithm that very obviously employs historical racial disparities in recorded crimes, and only gets its answer correctly about 20 per cent of the time. Our already-flawed system of incarceration would devolve into its most inhumane core if it was to be automated using similar algorithms.

Visualize the future, a world where the rich continue to get richer, and the poor continue to get poorer. But in this brave new world, the rich can accumulate capital independently – resulting in unbelievable levels of wealth by untethering from human labour. Without the side effect of paying humans, or, in that same regard, without paying for the dignity of the human worker, the rich will become rampantly richer.

While this level of dystopianism borders on fictitious, it is really just a matter of our limitless technological strides stepping in line with what the wealthy and powerful have been doing since the dawn of time: using their position of privilege to oppress others.

While some might fear the robot revolution because of the ethical ramifications of humanoid androids, there are economic implications that lie a little closer to our livelihoods just around the corner.