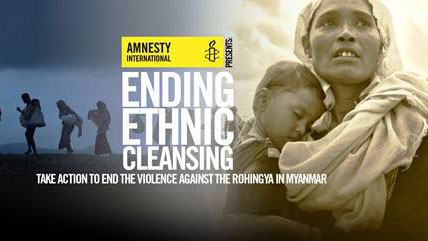

Amnesty International and the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization of Manitoba (IRCOM) hosted apanel discussion examining the persecution currently faced by the Rohingya peopel in the northern part of the state of Rakhine on Nov. 1.

Humaira Jaleel, co-chair of Amnesty Iinternational-Group 19 and one of the panelists, described “unlawful killings, mass murders, massacres, sexual violence [against] women and girls,” and the “burning of villages” as some of the recent documented dangers faced by the Rohingya in Myanmar.

The crisis and international response

According to a citizenship law passed in 1982, Myanmar does not recognize the Rohingya as one of the county’s 135 official ethnic minorities, and denies them basic rights including the right to work, study, marry, practice their religion, own property, participate in the electoral process, travel, and receive health care.

Jaleel said the extreme violence began when members of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army attacked border officials. The response of the military was “A blanket policy of criminalizing the whole entire population,” rather than focusing on the perpetrators of the attack or finding solutions to the abuses faced by the Rohingyas.

She said that although other ethnic minorities were also affected, it is the Rohingyas who have suffered the greatest persecution.

“There are towns where women and girls are separated from their men, and all the men were killed […] burning of villages, and these are not just burning of certain houses,” Jaleel said during the event. “We’re talking about entire villages that have been burnt, with sometimes, people inside them, and these are in hundreds.”

Jaleel added that, to make matters worse, the entire country, “especially Rakhine state,” has been sealed off from journalists, and more importantly, “the NGOs” and “humanitarian agencies” who would have otherwise provided aid to the fleeing community. Jaleel added that due to lack of access into the country, Amnesty International has been unsuccessful in investigating the matter.

“Amnesty has been trying to research what happened, find out what happened, but because Myanmar has closed its borders to journalists, to any NGOs, to any humanitarian aid agencies, there’s no way of actually researching and finding out what happened,” Jaleel said in an interview.

She added that since access to the country had been blocked off, obtaining accurate information on the current state of events in the country is extremely difficult.

“How do we know all of this when there is a complete blockade of Myanmar,” she asked.

“From witness accounts of hundreds of people, from satellite images, from the data, from the photos and videos that have been collected and […] sent to experts who have examined them, and all have given to the conclusion that there are crimes against humanity that are happening in Myanmar.”

Jaleel called on the United Nations Security Council to adopt a series of measures aimed at mitigating the situation.

“We’re also asking the UN Security council to also put an arms embargo, not to give any military assistance and also to have financial sanctions on the people who are responsible for these acts,” she said. “Because the problem is the military is not answerable to the civil government.”

She commended the international community for the positive response on the issue both within the continent and beyond. She mentioned that Pakistan, India, the Philippines, Canada, and the United States, among other countries, have shown immense support.

“Generally, other countries actually have recognized what’s happening,” she said. “On Oct. 29, there was a solidarity day where there were rallies and demonstrations happening all over United States and in Canada, but then actually turned into a week of solidarity.”

Canada’s role

Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s state counsellor, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and an honorary citizen of Canada, has been criticized for her failure to stand up for the rights of the Rohingya despite Prime Minister Justin Trudeau imploring her to condemn the violence. This has lead to the circulation of an online petition urging Trudeau to revoke her citizenship.

Jaleel said the Canadian government has a role to play in bringing awareness to the hardships faced by the Rohingya.

“In a country where we enjoy so many freedoms, we should be able to raise our voices for those who are being persecuted,” Jaleel said. “We want the Canadian government to actually do something about it. We’ve heard words, but now it’s time for action.”

Shauna Labman, an assistant professor at the U of M’s Robson Hall and another panelist at the event, said that while advocating for one group of refugees, other refugee groups must not be left out of the conversation.

“I think we have to push away these blinders, push beyond seeing particular groups,” she said. “And yet at the same time, recognizing the need to advocate for particular groups. Recognizing the need that some groups need a bigger, louder voice in particular moments.”

“Beyond signing petitions, possibly donating to charity and speaking out, keep in mind that there are other groups on the ground here in Winnipeg, either through resettlement or through asylum claims who are coming here and they need support just in terms of general humanity,” she added.

Labman said that at this moment, a “bigger, louder voice,” should be used for the benefit of the Rohingya people.

“So right now the Rohingya need our voice,” she said. “But we have to make sure that when we’re using that voice, we’re not using it to the exclusivity of other groups that need it.”