When the Manitoba PCs were seeking a mandate in the 2016 provincial election, they campaigned on a commitment to not cut frontline services. Other than that broad promise and a proposal to reduce ambulance fees, the PCs largely kept the focus off of themselves and off of specifics. They were looking to brand themselves as reasonable centrists after repeated losses campaigning from the far right.

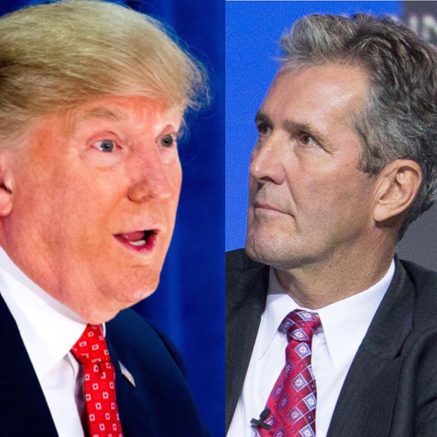

But with a recent announcement related to regulatory cutbacks, the PCs are showing their true colours: Trump orange.

The government has announced plans to draft legislation mandating the government cut two regulations for every one they introduce, a ratio that is supposed to drop to one-for-one after 2021, according to Deputy Premier Heather Stefanson.

The announcement should sound familiar to Manitobans, because it’s the same two-for-one policy announced by Donald Trump in his own 2016 election campaign, and the same one he signed an executive order to implement Monday.

Canadians – along with most of the rest of the world – have shown disdain for Trump, because, among other things, the new president is an unrepentant liar with no interest in governing and plans to dismantle regulations that protect everyday Americans. But despite this, Manitobans don’t seem to have reacted much to the news about the same Trump policy being proposed here.

It’s understandable that the rise of an authoritarian figure below the border is drawing our attention more than dry discussions around regulation and their impacts on everyday people, but it’s still critical that we recognize this for what it is: a stupid idea.

Laura Jones, executive vice president of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, was quoted about the significance of the regulation ratio by the CBC.

“Too many regulations is like having too many clothes in an overstuffed closet. What you’re doing with your two rules out for every one rule in is [you’re] cleaning the closet in Manitoba … [your] one-in-one-out is about keeping the closet clean.”

The problem is, regulations aren’t like clothes. If you have 10 shirts, they all serve the same function and are essentially interchangeable (at least for the fashion-unaware, such as myself). Regulations aren’t interchangeable though. They’re designed to meet specific needs. A regulation that protects water safety isn’t interchangeable with a regulation that prevents fire hazards in residential housing. Cutting one because you’re introducing another doesn’t make any sense, and cutting two is worse still.

Some Manitobans may have had frustrating experiences running up against individual regulations, but that doesn’t mean they’re unnecessary. And even if some were, overall, the system does work. If there are individual regulations that don’t make sense, people can approach their elected officials and raise concerns, and the government can repeal them. But the idea of setting up an arbitrary ratio independent of the regulations at hand shows the PCs don’t understand what government is for.

Its primary purpose should be to protect citizens against private interests and ensure a certain quality of life. The most common manifestation of that for government is regulating activities that might be damaging to the common good or threatening personal rights. This often means regulating corporations, with whom the profit motive is often pinned against someone else’s interests. For example, if you’re the owner of a business, you can make a larger profit if you don’t pay the costs required to make a workplace meet minimum levels of safety. The same argument can be made in terms of consumer protection with examples like food handling or processing regulations, or safety measures incorporated into automobile design. In these cases, government’s responsibility is to ensure private businesses are held to a standard that protects workers and citizens.

In order to recognize how useless this proposed legislation really is, it’s worth considering the best- and worst-case scenarios.

A theoretical worst-case scenario with the two-for-one proposal has the government unnecessarily struggling to pick between cutting two vital regulations like accessibility standards for new buildings and food inspection standards when they need to introduce another new regulation. A conservative defence of the proposal would likely argue that many regulations aren’t as critical as those two examples and that we could afford to lose those other ones. But if that’s the case, why wait to remove them?

Now that the PCs are in government, they’re free to look regulations over, assess them on their individual merit, and phase them out if they deem it necessary (and can effectively argue their case to the public and stakeholders).

A best case scenario for the effectiveness of the legislation would be if it serves as a reminder to the government to keep looking for useless regulations to remove – regulations they could still remove without this legislation. However, it would only be binding until the government of the day decided to repeal it, and this still assumes that the government will only ever run into unnecessary regulations to cut.

The notion of a law mandating removal of regulations based on an arbitrary ratio signals an ideological distaste for regulations and the role of government; it might be a portent of a more Trump-like province moving forward. Manitobans should keep their eyes peeled.