Researchers have developed an antibody-like molecule which may help in the fight against the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

The molecule, named eCD4-Ig, was designed to target parts of HIV that do not change very often. These parts are involved in how the virus attaches onto our cells and establishes an infection.

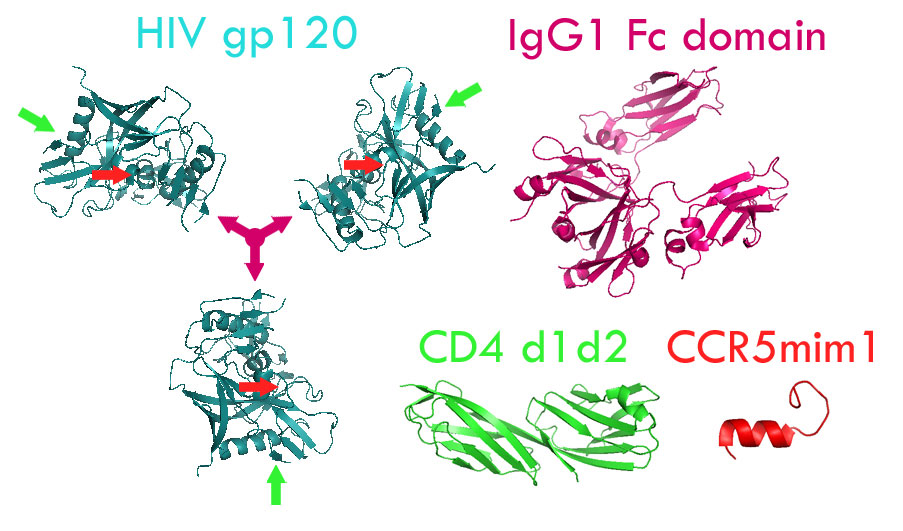

When an HIV molecule infects a human cell, it uses its gp120 protein to attach to the target’s CD4 surface molecule. Once docked, the virus then attaches to a second surface molecule CCR5. This interaction allows the virus to then enter the cell.

The molecule eCD4-Ig is comprised of a portion of antibody attached to pieces of both CD4 and CCR5, allowing it to bind to the sections of HIV needed for cell attachment. This binding effectively neutralizes the virus.

Molecule eCD4-Ig was developed in a collaboration between 33 researchers from more than a dozen institutes, spearheaded by Michael Farzan of the Scripps Research Institute in Jupiter, Florida.

The molecule provides an alternative imagining of HIV vaccination. Most vaccination efforts have been focused on delivering effective, broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) to cells.

As part of the study, the researchers tested the molecule’s ability to hold off infection from increasing doses of intravenous virus in four rhesus macaque monkeys. They did this by using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy vector.

The normally harmless AAV is further modified to disturb its normal viral lifecycle. This allows researchers to use the viruses to inject desirable genes into target cells without much worry of side effects.

More than 80 per cent of individuals are infected by AAV during childhood. You have probably never noticed because AAV does not cause illness.

Adeno-associated virus-based gene therapy has been the basis of a number of clinical trials since its first usage in 1994. Out of the hundreds of humans who have received AAV treatment, only a few have had serious adverse reactions.

The rhesus macaque monkey experiment did not use HIV itself, but a modified form of the simian immunodeficiency virus, a close relative to HIV that infects monkeys. The modified virus, dubbed SHIV, contained elements of both viruses.

The eCD4-Ig-carrying AAV vectors were injected into the quadriceps of the four monkeys.

The monkeys expressed eCD4-Ig for the entire duration of the 40-week experiment. In theory, eCD4-Ig introduced through AAV gene therapy may be expressed for the lifetime of an individual.

Molecule eCD4-Ig protected all four monkeys from SHIV infection. Four control monkeys that did not receive eCD4-Ig became infected by the same viral doses.

One major concern that arises whenever you place a foreign molecule into an individual is the potential rejection by the host’s immune system. The monkeys did not show a considerable immune reaction to eCD4-Ig, especially when compared to the immune reactions seen against bNAbs.

Another advantage eCD4-Ig has over bNAbs is that it is specific to a wider range of HIV strains. Because eCD4 contains elements of both CD4 and CCR5, it will hopefully be harder for HIV to mutate its way around the molecule, especially when compared to bNAbs, which typically only target one element of the virus.

Molecule eCD4-Ig only prevents HIV from infecting new cells. Unfortunately, it does nothing for cells that have already been infected.

When HIV infects a cell it makes a copy of its genetic material and inserts it into the human DNA. It is the perfect hiding spot for a virus that is difficult to get rid of.

Other treatments would still be needed to target the integrated viruses.

As well, the researchers have not yet tested eCD4-Ig’s ability to protect the monkeys from mucosal infections, the most common route of HIV entrance, which typically occur during sex.

Even though the results show that eCD4-Ig has lots of potential, bNAbs still show a lot of promise in the fight against HIV. Our best course of action against the virus is a comprehensive one. Molecule eCD4-Ig may be another reliable option for us.