We’ve all heard some variation of it by now: “Of course I believe in freedom of speech, but…” In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo shootings and the conversation which has ensued, we should be careful to consider the root of any arguments against a full and robust right to freedom of expression.

To argue that satire should be censored because offence might be taken is to misunderstand satire. If you misunderstand satire—and satire, like all humour, can have crude manifestations—then an explanation of it will not help you. In a 2007 court ruling a French court ruled that Charlie Hebdo‘s comics did not attack Islam. It found that their comics targeted a specific group–extremists–and were not hateful.

To argue that positions can be freely taken and expressed until some line is crossed is to argue that boys can wear any colour they want except for pink. If you have no pity for the dead cartoonists, have pity for the boys dead for wearing pink, who also sought nothing less than free expression.

To argue that artists, intellectuals, and the press should act according to the standards of any religion that they themselves do not profess is to argue for replacing “freedom of speech” with “freedom from speech.”

To argue that it is offensive to “Islam” to do something that is expressly prohibited by less than the totality of that religion, is to paint almost two billion people with one coarse brush, and to unthinkingly give in to lingering colonial tendencies to ascribe easy traits to a monolithic “other.” There is a rich tradition of illustrations of Muhammad, which are not prohibited in the Quran so long as they are not idolatrous.

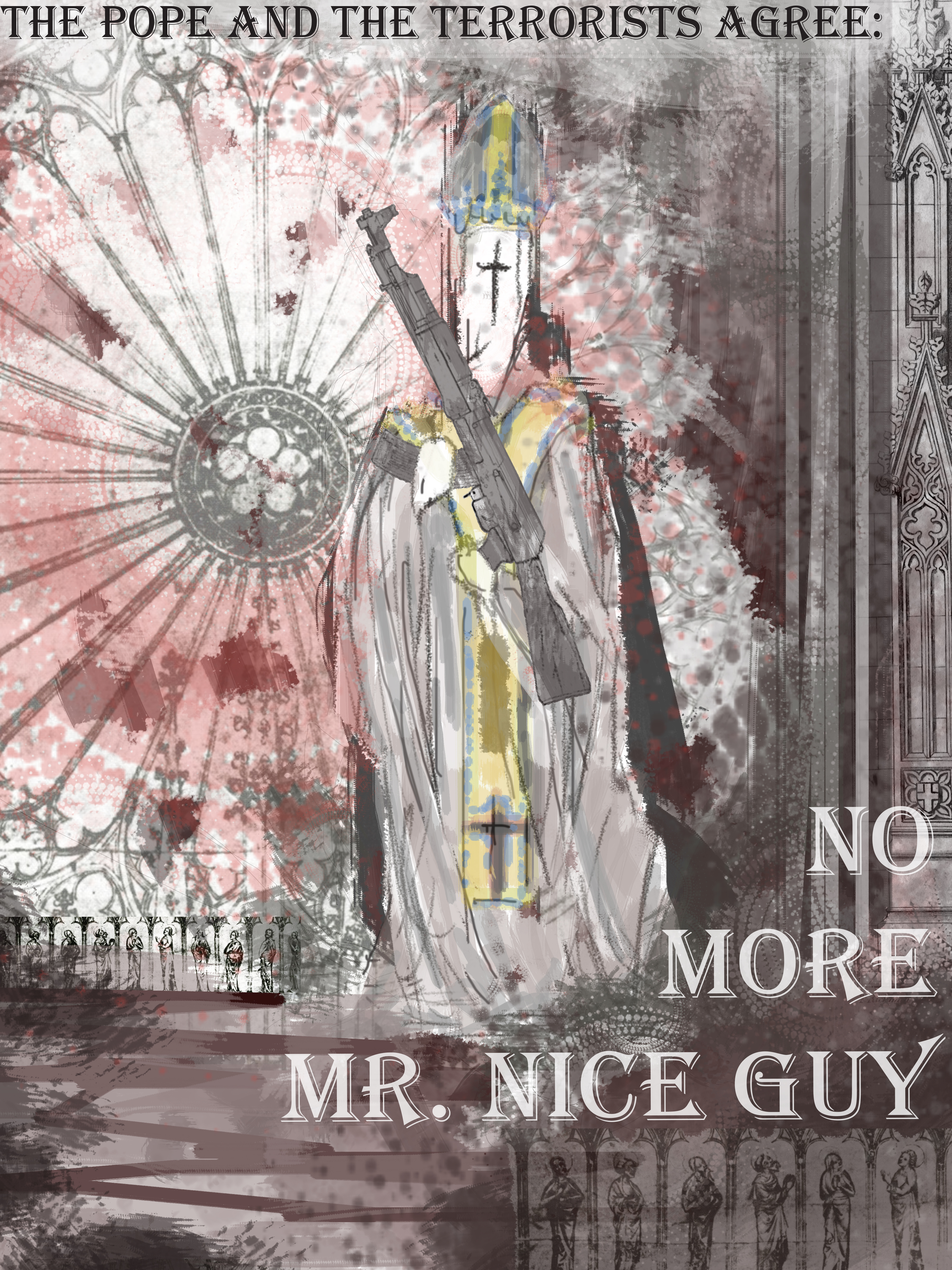

To argue that images (and what are images but fluid ideas temporarily frozen for easier digestion?) deemed offensive by some should not be reproduced, so that all people may judge for themselves whether they are offensive, is to assume that all people are easily offended, and that the easily offended will be satisfied with eliminating the images while letting the ideas flow freely.

To argue that freedom of speech, expression, or belief can be fully exercised, by everyone—and to believe that feelings cannot be hurt, and offence not taken or given—is naïve. It is to hope for easy answers to complex issues, or worse, to hope that complex issues will not arise.

Images serve to bring up ideas in us, from the highest to the lowest of thoughts and emotions. To censor images because we do not like the ideas they bring forth is to deny that those ideas exist in us. If we see an image and our first thought is negative, we should thank the image-makers for what they have told us about ourselves. We should not, as a knee-jerk reaction, assume that others cannot handle negative thoughts, or weighty ideas.

There is no particular need for free speech, or at least for a particularly robust form of it. Words and images are censored all over the world. This is sometimes done to stifle hate, other times dissent. A nation can still be powerful, and a culture fruitful, without free speech.

But doing away with free speech comes with a price, one that those least willing to pay are perhaps the ones who feel most entitled to air an opinion on editorial cartoons. “Vivre Libre ou Mourir.” If you do not approve of how the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo expressed their beliefs, remember that they died for the principle that you could say, “Fuck those guys.”