In what the prosecuting lawyer is calling a “precedent-setting” move, a 17-year-old girl from British Columbia has been convicted of child pornography charges stemming from her distribution of nude photos of another girl via text message.

The charges came after the accused reportedly distributed photos of the ex-girlfriend of her then-17-year-old boyfriend, and threatened the victim repeatedly online.

According to Chandra Fisher, crown prosecutor for the case, the accused took issue with the contact between her boyfriend and her boyfriend’s ex-girlfriend.

The judge in the case called the messages “mean, rude, and antagonistic,” and stated that the images shared by the accused fall “within the definition of child pornography.”

The court was informed that the accused intended to both humiliate and threaten the victim.

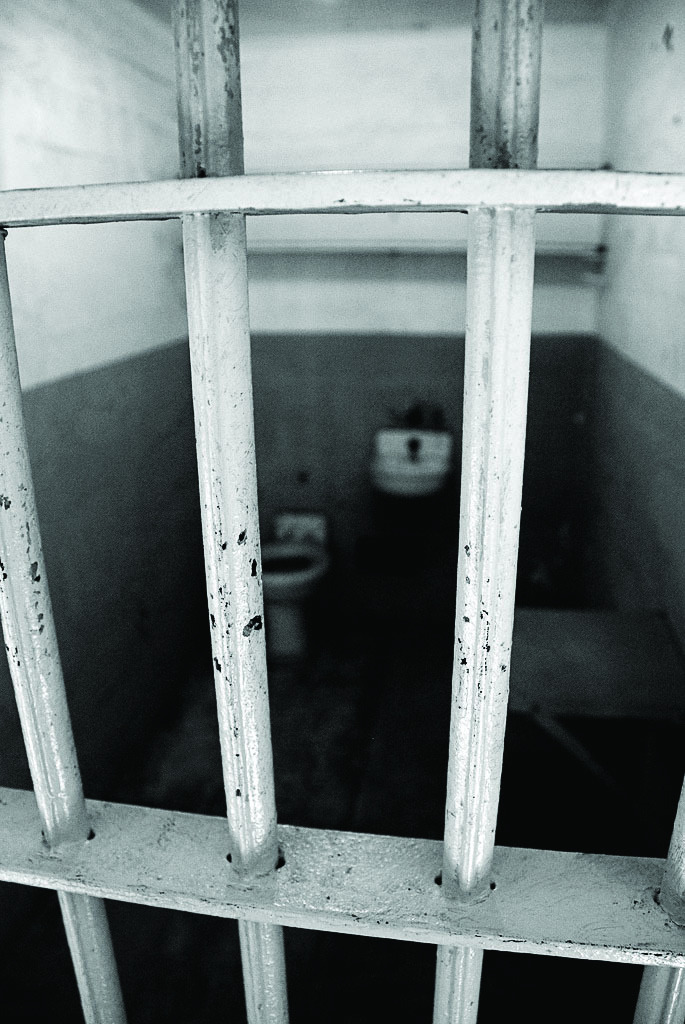

The accused, who was 16 at the time of the 2012 offence and thus cannot be named, was charged and found guilty of uttering threats and distributing child pornography. She is currently out on bail and awaiting sentencing.

Christopher Mackie, lawyer for the accused, said he plans to challenge the ruling on a constitutional basis under the argument that since it is legal for adults to send “erotic images” to each other, it should be legal for teens to “sext.”

“Child pornography laws were intended to protect children, not to persecute them,” Mackie told the CBC.

Neil McArthur, associate director of the centre for professional and applied ethics and associate professor of philosophy at the University of Manitoba, agrees.

“The law was written with a clear intention, prosecuting pedophiles, and was never intended to apply to such cases. The problem is that our laws haven’t caught up to the problem of sexting. We need specific laws tailored to this sort of situation, so that the police aren’t forced to use whatever laws they can find to prosecute people who do it.”

It is a problem that government officials tried to remedy in the proposed Bill C-13, a bill that has been met with resistance from many who fear it will impose on their privacy.

Opponents claim that while the bill is right in its attempt to criminalize cyberbullying, the rest of its contents are too similar to Bill C-30, which was vehemently opposed for a perceived potential for privacy violations in the form of online surveillance.

“Much of Bill C-13 is almost a cut-and-paste of C-30,” wrote the BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association.

“The major difference is that the overly broad surveillance provisions are rolled up with provisions dealing with a genuine problem (cyberbullying). Can we now expect Justice Minister Peter MacKay to stand in the House [ . . . ] and declare ‘you can stand with us or you can stand with the cyberbullies’?”

The debate is capable of drawing out the passing of the bill for months, which, as McArthur pointed out, does little to help current victims.

“Quite frankly, lawmakers need to get off their asses and start writing laws that deal with our modern age,” said McArthur.

“Yes, sexting is a relatively new problem, but it didn’t start happening just yesterday. Legislatures have had several years to deal with it, and they are only now starting to.”

Referring to cases such as that of Amanda Todd, Rehtaeh Parsons, and Rebecca Ann Sedwick, McArthur said, “People need to start pressuring their elected representatives to get moving. It’s a huge problem, which is destroying people’s lives and, in some tragic cases, leading to suicide.”

For anti-bullying resources, visit Prevnet