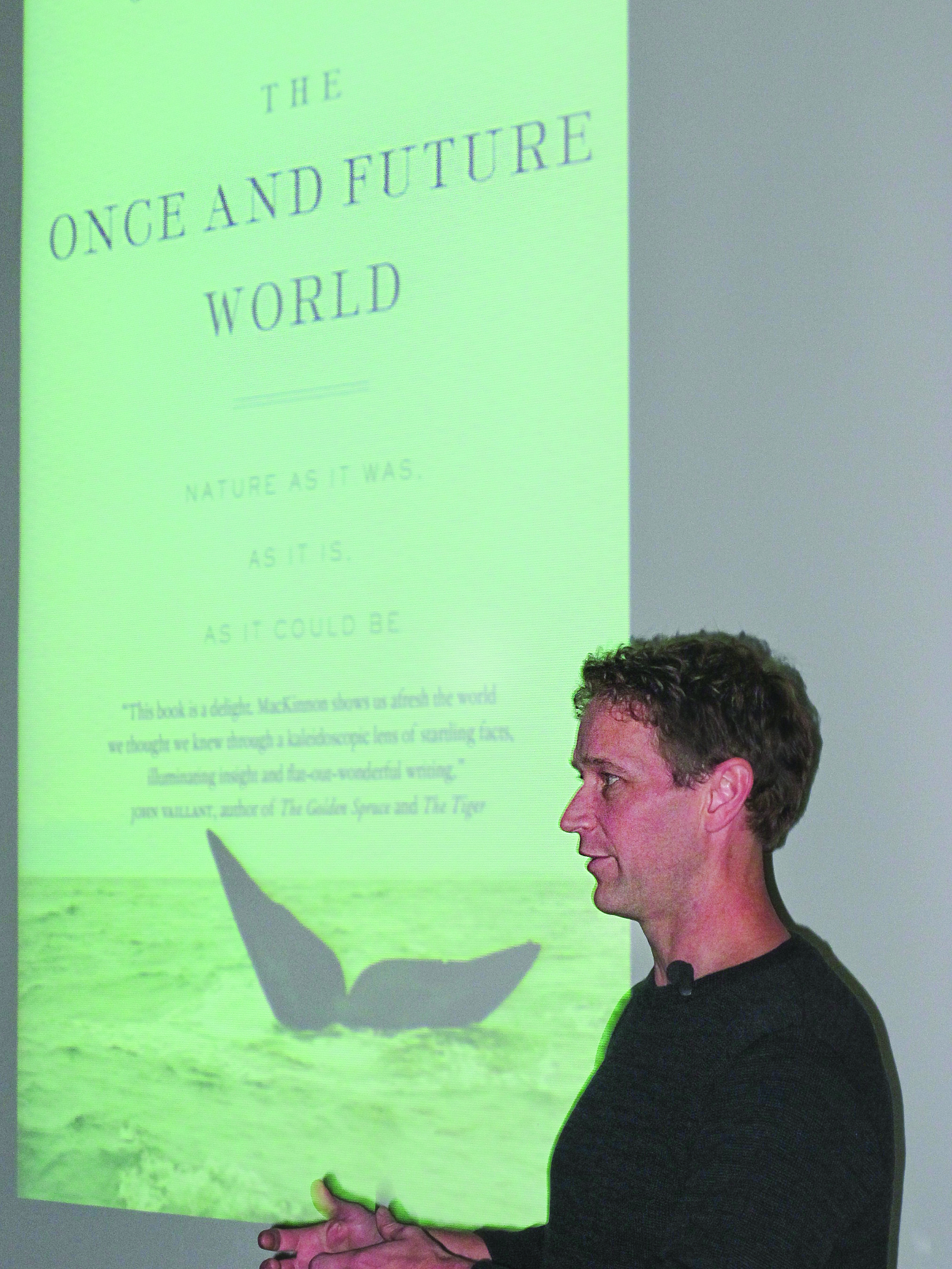

Have you ever examined your relationship with the natural world? J. B. MacKinnon visited the U of M campus on Tuesday, Oct. 15 to promote his new book, The Once and Future World. The book examines the history of nature, the notion of personally reconnecting with nature, and the concept of “rewilding.”

MacKinnon spoke with UMFM on Tuesday regarding the recurring themes in his book. The idea for The Once and Future World was planted when MacKinnon revisited his hometown. As a young child, he was able to roam the adjacent expanse of grasslands, but upon returning as an adult he found that much of the area had been converted to suburban developments.

Reflecting on the visit to his hometown, MacKinnon said, “It just triggered this desire to know more about the history of the landscape I grew up on in general.” He discovered that not only were there a number of species now missing from the area, but that people had forgotten about them.

“Their presence had been totally forgotten,” he said. “Growing up, no one ever mentioned to me any of these missing animals.”

During his talk, MacKinnon proposed the “three ‘R’s”: remember, reconnect, and rewild.

The theme of remembering nature and exploring the history of nature is present throughout the book. MacKinnon suggested that, although students learn many forms of history in school and through pop culture, the history of nature is often overlooked.

“[Natural history] is perhaps our most forgotten form of history,” he said. “It’s incredible how quickly people lose sight of what the natural world was like in the past, and it frequently does happen within a single generation.”

Losing sight of the changing natural world occurs all too easily and frequently, according to MacKinnon. He invoked the concept known as “shifting baseline syndrome” to explain how this forgetful feature of the human condition distorts the way we measure the generational degradation of nature.

“Each generation is looking at the world that they grow up in and then measuring the degradation of that world against their own life experience. But then, along comes another generation and they do exactly the same thing, starting from their new point. The degraded state of nature for one generation becomes the normal state of nature for the next,” he said.

MacKinnon proposes “rewilding”-the creation of environmental conditions that accommodate and encourage the existence of wildlife communities in urban areas-as a possible solution to this generational myopia.

According to MacKinnon, throughout history people have farmed animals to the point of extinction; however, we need not continue to do so in the future.

“I think what history indicates is that we all too often get carried away with whatever direction we’re headed in, so we become persuaded that we need to, [for instance], eliminate predators from the landscape because they threaten certain of our interests. So we go about destroying all of them, everywhere. It becomes this relentless pursuit, almost comparable to a religious mania.”

MacKinnon described the importance of fostering a “meaningful” social relationship with wildlife, one in which we can live alongside each other in harmony. He noted how, for him, nurturing this relationship began as a simple act of mindfully observing his surroundings in parks and urban areas.

“If we allow nature to become meaningless to us, then that will certainly be the nail in the coffin in the human relationship to the natural world,” said MacKinnon.