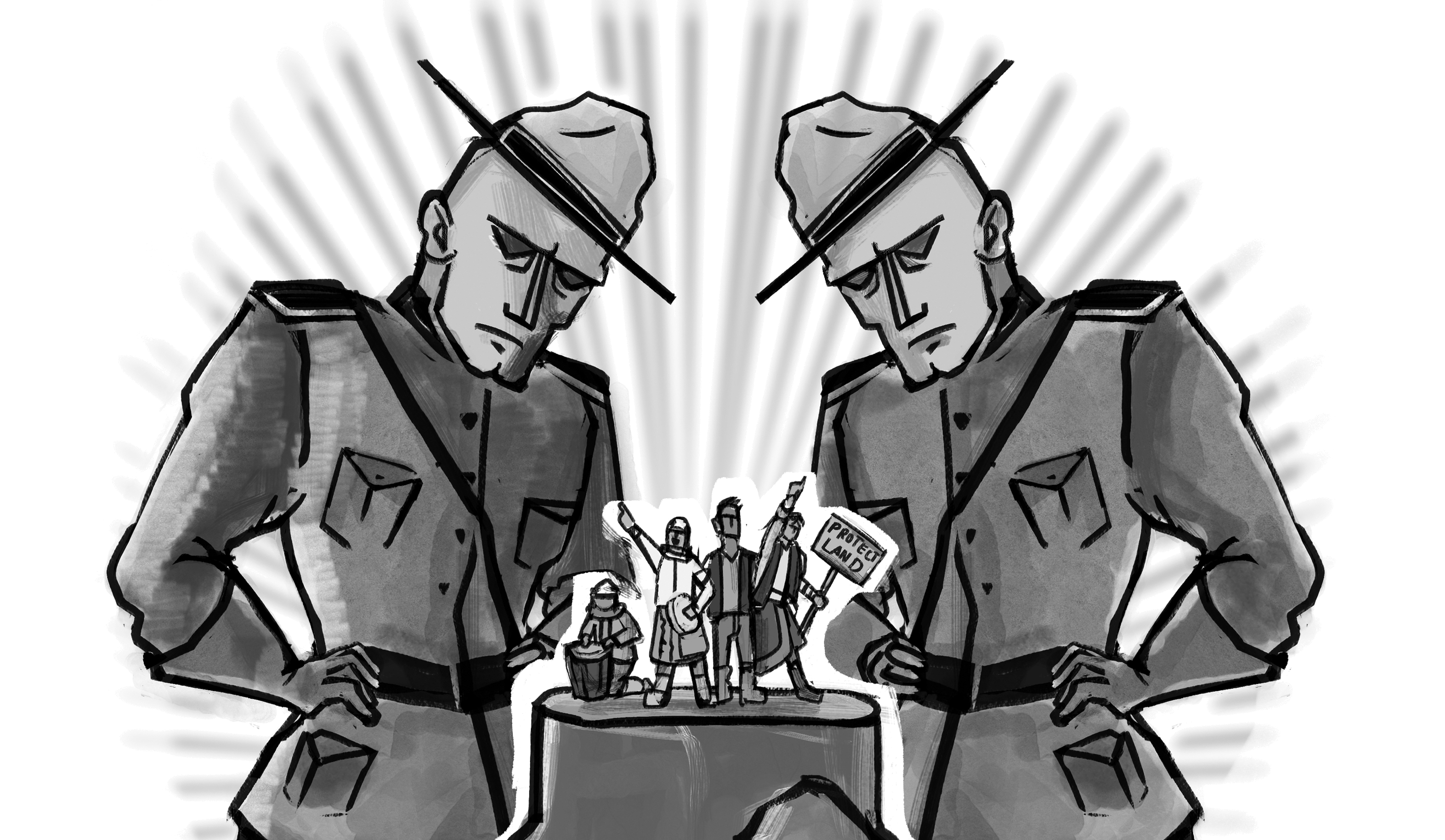

Last week, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) set up an armed checkpoint controlling access to Unist’ot’en — a camp of Wet’suwet’en Nation land defenders resisting the construction of a natural gas pipeline through traditional territories.

As police block access to the camp for the second time in a year, the so-called era of reconciliation is coming into sharp focus — and it looks awful familiar.

The pugnacious police response. The refusal of British Columbia NDP premier John Horgan to even meet with the five hereditary chiefs opposing the project. The elevation of economic expansion above the rights of entire communities.

The whole scenario harkens back to what should have been watershed moments in Canadian history. From Oka to Ipperwash, the events unfolding on Wet’suwet’en territory draw from a tired blueprint that moves further away from, not toward, reconciliation.

The Coastal GasLink pipeline is part of a $6.6 billion project to bring natural gas from northeastern British Columbia to the coast and has been approved by the provincial and federal governments. Five elected Wet’suwet’en band councils are also in support.

But hereditary chiefs have consistently opposed the construction and set up blockades to stop work from going forward more than a year ago. The project has also been panned by B.C.’s human rights commission and the UN committee on the elimination of racial discrimination.

In early 2019, the RCMP set up a checkpoint and was prepared to use lethal force against the land defenders, according to a report from the Guardian published in late December.

According to the report, police command instructed officers to “use as much violence toward the gate as you want.”

This belligerent escalation of colonial violence upon Indigenous populations asserting claim to traditional land is old hat in Canada.

In the summer of 1990, the Mohawk of Kanesatake waged a 78-day standoff after the town of Oka, Que., moved to develop traditional territory that included a burial ground.

The project called for the construction of condominium units and the expansion of a golf course from nine to 18 holes in a common area of the Mohawk of the Kanesatake reserve known as the Pines. The first nine holes were constructed in 1961 amidst protest and after a Mohawk claim to the land was rejected.

Mohawk warriors established a blockade in July 1990 and after refusing to abide court orders to dismantle the roadblock, provincial police were dispatched and attacked protesters with tear gas and concussion grenades.

In the ensuing gunfight, Quebec provincial police officer Cpl. Marcel Lemay was killed.

Tensions further escalated through the summer as police established their own roadblocks and Indigenous protesters barricaded the Mercier Bridge, severing the Island of Montreal from the city’s suburbs.

The RCMP and military were eventually called in and under intense pressure the protesters stood down on Sept. 26 — but not before a soldier’s bayonet found the chest of Waneek Horn-Miller, a 14-year-old who was carrying her infant sister. She recovered, was named co-captain of Canada’s first women’s Olympic water polo team and remains an activist today.

The land was only finally signed over to the band in July of last year.

Five years after the crisis in Oka, this time in Ontario, it was an Indigenous protester who was killed after Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) Sgt. Ken Deane shot Anthony (Dudley) O’Brien George. Deane was convicted of criminal negligence causing death in the spring of 1997.

George was killed as members of the Kettle and Stony Point First Nation occupied Ipperwash Provincial Park and a military office in protest of the federal government’s failure to return the Stony Point reserve to Indigenous control after appropriating it for a military camp in the 1940s.

The OPP descended on the protesters in force, deploying helicopters, boats and undercover officers for surveillance while advancing emergency response, tactical and crowd control units shielded behind armour and weapons.

An inquiry later found that officers attending the scene harboured racist views and were ignorant of Indigenous history. It was also critical of the provincial government for maintaining the occupation was illegal and refusing negotiations or third-party mediators.

The inquiry also heard that then-premier Mike Harris declared “I want the fucking Indians out of the park” hours before George’s killing, though Harris denies the remark.

But Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised to be different.

After receiving the final report of the truth and reconciliation commission’s investigation into Canada’s Indian residential school system in 2015, he said “This is a time of real and positive change” that marked a “total renewal of the relationship between Canada and Indigenous peoples.”

“We have,” he said, “a plan to move toward a nation-to-nation relationship based on recognition, rights, respect, cooperation and partnership, and we are already making it happen.”

He lied.

More than three years later in 2019, the Wet’suwet’en protest was broken up when RCMP officers clad in army fatigues dismantled the Wet’suwet’en checkpoint and arrested 14 people.

It should come as no surprise. This is the same man who, as a member of parliament, boxed and publicly cut the hair of a “scrappy tough-guy senator from an Indigenous community” because, as Trudeau told Rolling Stone, he represented “a very nice counterpoint.”

Trudeau acknowledged the cultural significance of hair to an Indigenous man, saying “That’s why I proposed it. When a warrior cuts his hair, it’s a sign of shame, so it’s very apropos.”

Indeed. And while Trudeau has, of course, signalled his regret for his choice of language and how his comments to Rolling Stone have “been taken,” his position as leader is clear.

As long as recognition, rights, respect, co-operation and partnership with Indigenous communities continue to be subordinated to the economic and paternal drive of the Canadian state, “reconciliation” serves as little more than political cover for the continuing colonial mission.