The recent announcement that the University of Manitoba is preparing for budget cuts has generated controversy including critical reaction from students and faculty at the U of M.

According to U of M president David Barnard, both academic and non-academic units are being asked to prepare for average budget cuts of four per cent this year and four per cent next year.

The cuts were outlined to faculty and staff as part of the university’s strategic resource allocation process which marks the beginning of annual budget consultation at the U of M.

According to Barnard, the cuts may be necessary given the difficult financial situation the university faces.

“We don’t yet know what the provincial grant will be, but whatever it is we need to be ready to respond to it,” Barnard told the Manitoban.

The annual provincial operating grant for Manitoba universities has increased by 2.5 per cent each year for the last two years.

Barnard argued that another 2.5 per cent increase in the grant is insufficient compensation for Manitoba having the third lowest tuition fees in the country. Provincial legislation passed in 2011 capped tuition in Manitoba at the rate of inflation.

“If [tuition fees] moved up to be comparable to fees at other universities it would mean a substantial increase in revenues for the university,” Barnard said.

Provincial government, opposition respond

According to Peter Bjornson, Manitoba’s new minister of education and advanced learning, the provincial government is not going to change its tuition policy as long as the New Democratic Party (NDP) is in power.

“We want to make sure that we have an affordable, accessible post-secondary system in the province,” Bjornson said.

“You can expect our policy [on tuition] to be consistent.”

Although Bjornson would not disclose how much the provincial operating grant for universities may or may not increase next year, he argued the NDP has provided generous funding for universities in the midst of an economic downturn.

“We were still in the throes of a global economic downturn when we brought in a 2.5 per cent increase in funding,” Bjornson said, adding that he hopes the university can avoid steep budget cuts just as the provincial government has avoided austerity measures.

“As government, we have our own challenges in terms of how we deliver our services, and we’re working very hard to ensure we can provide the best possible services with our economic challenges and we would hope that the university would do the same.”

Wayne Ewasko, education critic for the Progressive Conservative Party of Manitoba, argued that steep budget cuts at the U of M are a product of distrust between the NDP government and Manitoba universities.

“You can promise the moon, but if you don’t have the funds to back it up, then what ends up happening? You end up having broken promises,” Ewasko said, referring to the NDP government’s 2011 vow to increase the annual operating grant by five per cent a year for three years, which the government reneged on in 2013.

Ewasko cited the U of M Front and Centre campaign, which seeks to raise $500 million in private donations for the university, as an example of how provincial costs can be offloaded onto post-secondary institutions.

“Whether it’s post-secondary institutions; whether it’s municipal governments; whether it’s taxpayers; they’re starting to figure out that they’re being downloaded on and so in order to get certain things done they’re going to have to start doing it themselves,” Ewasko said.

Faculty tensions re-emerge

Just over a year after the University of Manitoba Faculty Association (UMFA) nearly went on strike over academic freedom issues, some faculty members have become concerned about deteriorating working conditions in lieu of the proposed budget cuts.

According to UMFA president Thomas Kucera, faculty members are animated around the issue.

Some faculty members will be attending a public student-led “Stop the Cuts” assembly on Nov. 26 organized by U of M students. The event will be held in conjunction with the Canadian Federation of Students-Manitoba, to “stop significant budget cuts at the University of Manitoba that could result in class cancellations, layoffs, program mergers or closures,” and a “general deterioration of academic options and quality.”

Much of the faculty opposition comes in response to a statement released about the cuts by Barnard on Nov. 14.

“We want to weigh carefully and understand the impact of reductions in different units in order to make spending cuts,” stated Barnard.

“These decisions will be made through consideration of unit and faculty plans and priorities [ . . . ] It’s important for people in both academic and support units to get involved in the process and provide their best ideas from their knowledge and experience with different areas of the university.”

“I didn’t really appreciate the appeal for us all to get together and decide how we are going to cut our own throats, or whose throats are going to be cut,” Kucera said, referring to Barnard’s statement.

“The campus is quite energized on this issue and I think Barnard stirred up a hornet’s nest.”

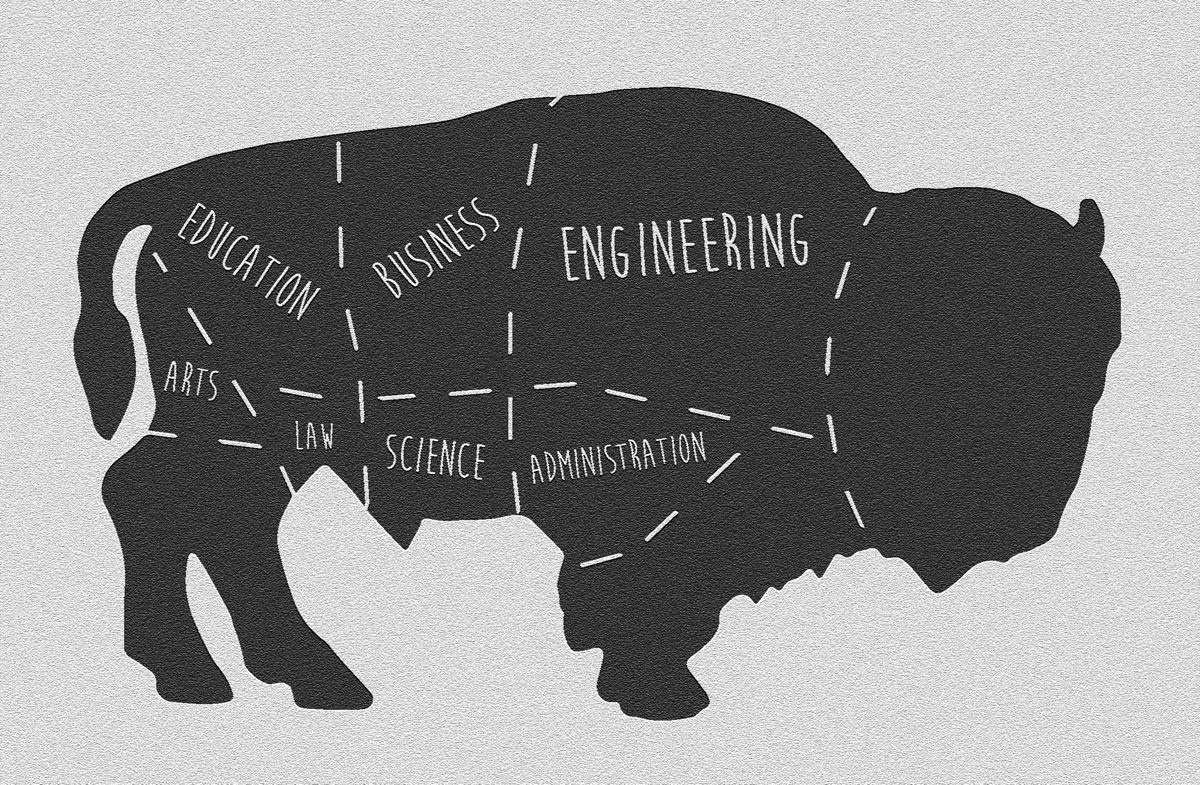

The University of Manitoba Faculty Association has conducted an analysis of the U of M operating budget for several years. After last year’s round of collective bargaining, UMFA concluded that faculties and academic departments were seeing limited growth compared to administration at the U of M.

According to UMFA’s 2014 summer newsletter, which tracked budget growth between 2009 and 2013, the budget for the office of the vice-president academic at the U of M increased from $18.5 million in 2009 to $25.8 million in 2013 – a 39.5 per cent increase.

During the same period, the science faculty budget went from $27.1 million in 2009 to $29.9 million in 2013 – a 10.3 per cent increase. “The increase to all faculties in the same period went from $260.4 million to $311.0 million” – an increase of 19.4 per cent.

The highest increase went to the office of the vice-president external, which saw its budget go from $5.6 million in 2009 to $11 million in 2013 – a 96.4 per cent increase. The vice-president external is responsible for marketing and communications, alumni, and donor relations.

According to Kucera, this budget disparity is the real culprit when it comes to any funding crunch experienced by the U of M.

“They have been transferring money from academics to administrative things,” Kucera said.

“It’s really a problem of allocation of money and if more resources were being allocated to academics, the cuts might not be necessary or they might not necessarily be so severe.”

Cameron Morrill, an associate professor of accounting at the U of M, has conducted extensive research on the financial reporting practices of Canadian universities.

In a series of articles published in the UMFA newsletter in the winter of 2010, Morrill described how surplus funds from the U of M operating budget were consistently spent on capital assets or allocated to specific provisions, such as equipment replacement or unit-specific projects.

By transferring operating surpluses into other areas, the U of M created a funding problem that did not actually exist within the purview of normal operating expenditures, Morrill said.

“The university has always argued that the government does not give them enough capital money for their needs [ . . . ] so a certain amount of money has to come from the operating fund,” he said, adding that the university ends up using operating surpluses to cover cost overruns on expensive capital projects.

Morrill added that increases in the budget for marketing and communications at the U of M have also contributed to the university’s financial woes.

“I think we end up spending a fair bit of money on advertising for what is, really, a fixed number of students and a fixed amount of donor dollars,” he said.

“At the end of the day, I think what happens is you end up with the same number of students as there would have been before, you end up with maybe the same amount of donor dollars as there would have been before, but you’ve thrown a whole bunch of money away on big billboards and advertisements.”

In response, Barnard argued that the U of M actively attempts to balance academic and administrative expenditures in line with what can be seen at other universities.

“It’d be like saying we’re going to buy clothes but we’re not going to buy food for a while, or we’re going to buy less food,” Barnard said.

“You might decide to squeeze part of your budget at some point, but eventually you have to keep the size of the different components of your budget in balance.”