Classes were suspended in Montreal due to increased student protests on Aug. 27. There were 47 cancelled classes at the Université de Montréal after tension amplified between students, police, and university administration.

On Aug. 28, 10 students faced charges and 21 people were detained due to protests as the classes to make up for the cancelled winter term commenced. Protesters allegedly assaulted security and police and were disrupting the classes, causing the university to suspend classes in anthropology, film studies, art history, East Asian studies, video-gaming studies, and comparative literature.

The police were called by university administration on Aug. 28, a move that, according to Alexandre Ducharme of FACÉCUM (the federation representing students at the Université de Montréal) was unnecessary. Ducharme states that the police measures were disproportionate since there were only 50 students protesting and yet 50 police cars.

The cancellation of classes was required, according to university administrators at the Université de Montréal, regardless of Law 12 (Bill 78), which stipulates that classes continue even in the case of student boycotts.

Protests also occurred at the downtown campus of Université du Quebec à Montréal, involving crowds of students moving through the university to different classrooms, emptying those in which the faculty had voted to keep striking.

There was immense tension between protesters and students in classes at this protest. Protesters entered a class filled with 15 students who continued with their lecture, despite the noise made by the protesters’ horns and the banging of pickle jars.

“I think I have the right to class and I’m staying. And we want to show them that this is what we want,” said student Amelie Bleau.

UMSU president, Bilan Arte, however, believes that these protests are an adequate response to the tuition hikes. Arte explains that successful campaigning requires students to put pressure on the government through an array of measures, including direct action.

“Considering the unconstitutional restrictions and threat of heavy fines placed on student protests by the Quebec government’s Bill 78, it is commendable that students continue to protest unfair government proposal,” says Arte.

The Université de Montréal was quiet on Aug. 29 as classes were cancelled, yet, the protests moved to the streets. Nearly 100 protesters marched through downtown Montreal wearing masks and occupying a building on Sherbrooke St., resulting in four arrests. Protesters concentrated on opposing tuition hikes and capitalism.

Some violence boiled over into the street as garbage cans were thrown and traffic pylons were tossed in the air, in one case striking a pedestrian.

Bill 78 requires that an itinerary of a demonstration be provided eight hours before the protest. Failure to do so resulted in four arrests on Aug 29.

Bill 78 is a student strike law that can impose individual fines up to $5,000 and $25,000 for an association of students or faculty. The Bill was passed through the Liberal government in May and arose as a major point of contention in the protests in Montreal and across the country.

Student protests, however, did not occur at all institutions. Classes resumed without incidents at junior colleges throughout Quebec and, according to the National Post, a large portion of students in the province have voted to conclude the strikes.

Solidarity is seen, however, throughout the country. Arte says that UMSU voted in favour of solidarity with the Quebec movement at the May annual general meeting of the Canadian Federation of Students, along with the majority of other student unions. Additionally, Arte explains that there was a unanimous vote from all the unions to condemn Bill 78.

The upcoming Provincial election on Sept. 4 is said to play a factor in the protests, either increasing or alleviating tension. Jeremie Bedard-Wien, spokesman for the CLASSE student association, believes that the main parties in the election are avoiding the topic of the student protests. He states that this demonstrates the distrust in politicians within the movement.

“They haven’t supported us much during the strike and we don’t expect much from them at all – and that is why we argue for sustained mobilization,” says Bedard-Wien.

The alleged distrust for politicians was evident when protesters arrived at a campaign event for Liberal leader and incumbent premier Jean Charest on Aug. 29. Charest has proposed the large tuition hike and has not revised his plans despite six months of student protests.

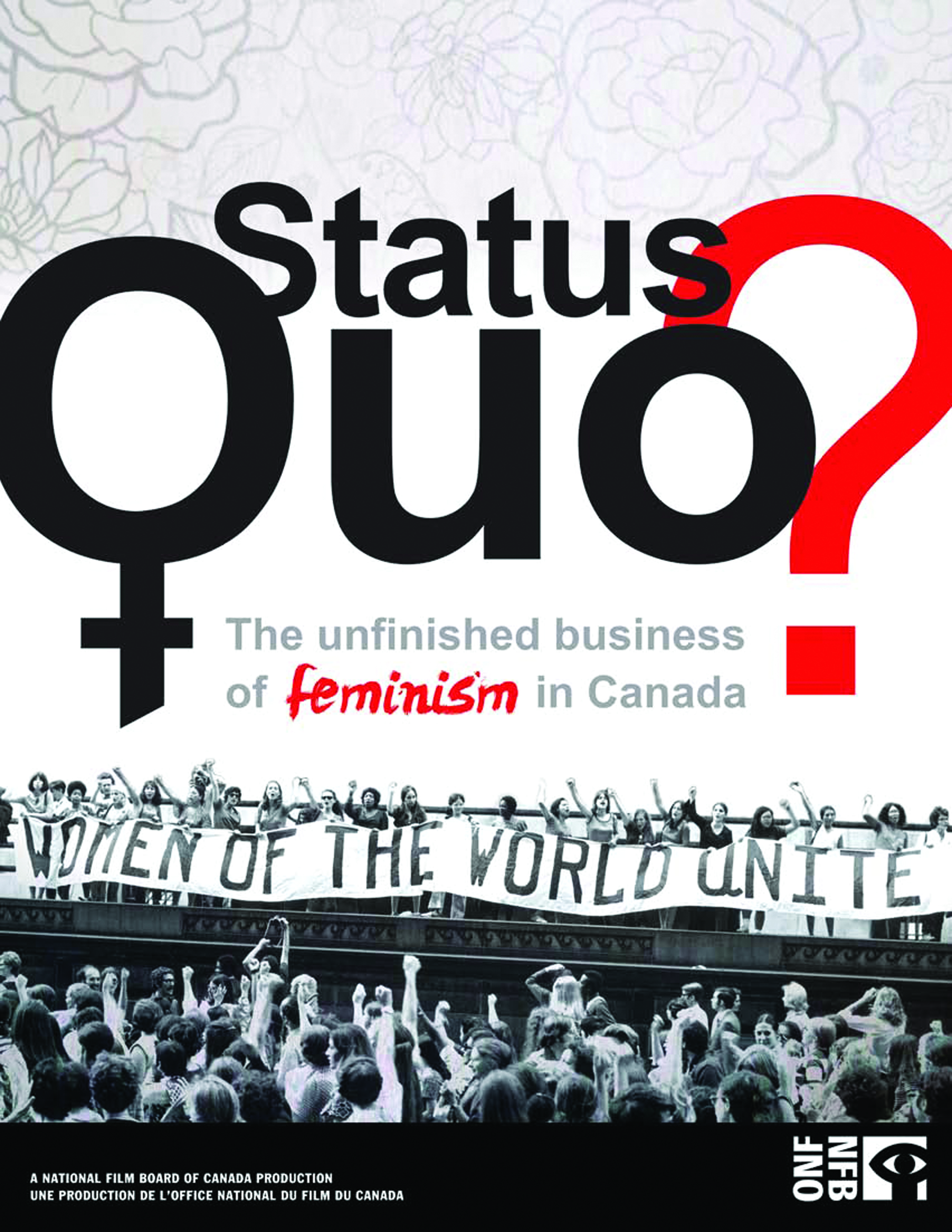

Charest was holding the event in his home riding of Sherbrooke, Quebec when the protesters arrived wearing the red square that has evolved as a symbol of unity for the Quebec student movement.

The demonstration included chanting of “Parti Libéral, parti patronal,” meaning “Liberal Party, party of big business.”

Police arrived and formed a line near the public market where the event was held, ensuring that the protesters did not enter. However, Charest cancelled the event citing concerns for safety.

Liberal opposition parties have other opinions on the tuition hike. The coalition Avenir Québec proposes a 45 per cent raise and Parti Québécois promises to cancel the hike all together.

A decisive conclusion to the protests has yet to be found. Arte explains that the issues will only get worse without looking at the root of the problems and solving the core issues.

“The provincial government in Quebec needs to sit down with the student representatives and commit to meaningful negotiations on tuition fees and related issues,” says Arte.

The student protests have been occurring on the 22nd of every month since February and originated due to a proposed tuition increase of approximately 75 per cent in the next five to seven years.